A few weeks back, I decided to do something about the low quality of experiments in modern chemistry and science sets; I posted to this blog some interesting science experiments, and some more-interesting experiments that could be done at home using the toxic (poisonous dangerous) chemicals available under the sink or on the hardware store. Here are some more. As previously, the chemicals are toxic and dangerous but available. As previously, these experiments should be done only with parental (adult) supervision. Some of these next experiments involve some math, as key aspect of science; others involve some new equipment as well as the stuff you used previously. To do them all, you will want a stop watch, a volt-amp meter, and a small transformer, available at RadioShack; you’ll also want some test tubes or similar, clear cigar tubes, wire and baking soda; for the coating experiment you’ll want copper drain clear, or copper containing fertilizer and some washers available at the hardware store; for metal casting experiment you’ll need a tin can, pliers, a gas stove and some pennies, plus a mold, some sand, good shoes, and a floor cover; and for the biology experiment you will need several 9 V batteries, and you will have to get a frog and kill it. You can skip any of these experiments, if you like and do the others. If you have not done the previous experiments, look them over or do them now.

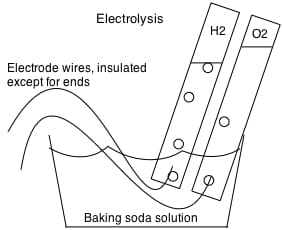

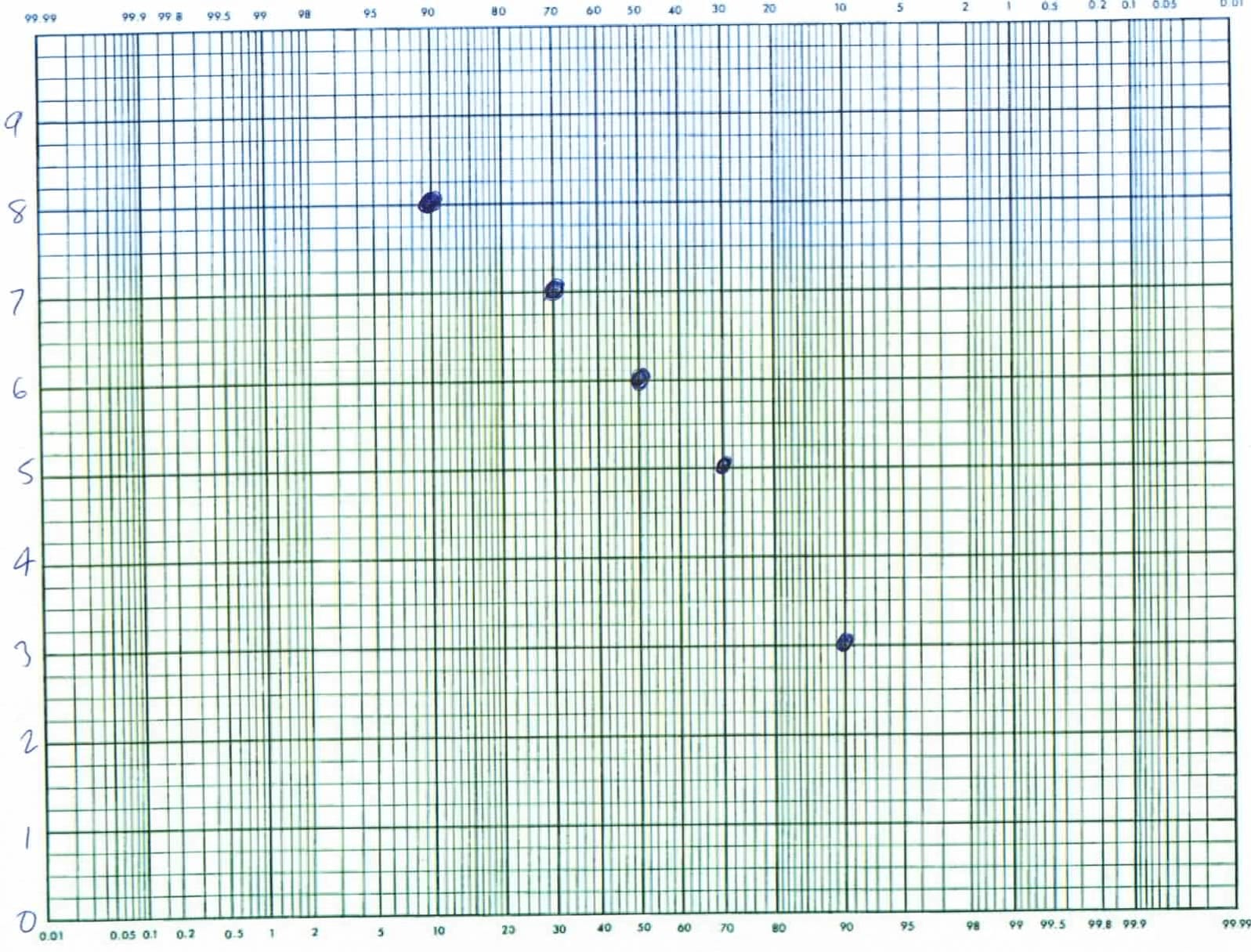

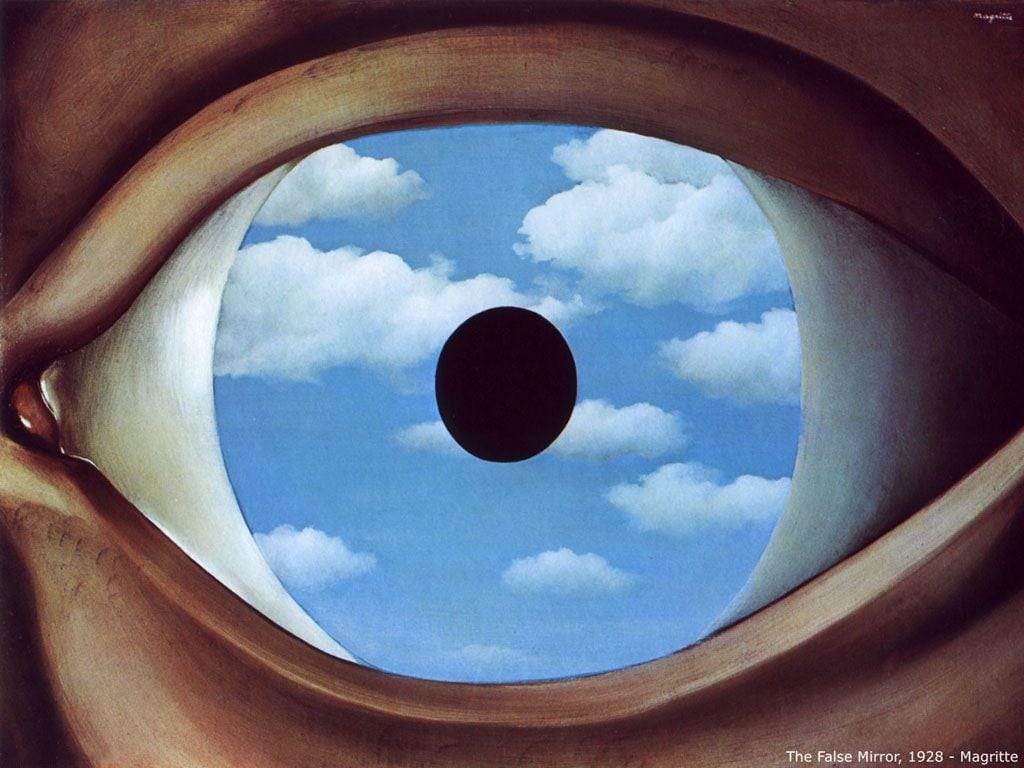

1) The first experiments aim to add some numerical observations to our previous studies of electrolysis. Here is where you will see why we think that molecules like water are made of fixed compositions of atoms. Lets redo the water electrolysis experiment now with an Ammeter in line between the battery and one of the electrodes. With the ammeter connected, put both electrodes deep into a solution of water with a little lye, and then (while watching the ammeter) lift one electrode half out, place it back, and lift the other. You will find, I think, that one of the other electrode is the limiting electrode, and that the amperage goes to 1/2 its previous value when this electrode is half lifted. Lifting the other electrode changes neither the amperage or the amount of bubbles, but lifting this limiting electrode changes both the amount of bubbles and the amperage. If you watch closely, though, you’ll see it changes the amount of bubbles at both electrodes in proportion, and that the amount of bubbles is in promotion to the amperage. If you collect the two gasses simultaneously, you’ll see that the volume of gas collected is always in a ratio of 2 to 1. For other electrolysis (H2 and Cl2) it will be 1 to1; it’s always a ratio of small numbers. See diagram below on how to make and collect oxygen and hydrogen simultaneously by electrolyzing water with lye or baking soda as electrolyte. With lye or baking soda, you’ll find that there is always twice as much hydrogen produced as oxygen — exactly.

You can also do electrolysis with table salt or muriatic acid as an electrolyte, but for this you’ll need carbon or platinum electrodes. If you do it right, you’ll get hydrogen and chlorine, a green gas that smells bad. If you don’t do this right, using a wire instead of a carbon or platinum electrode, you’ll still get hydrogen, but no chlorine. Instead of chlorine, you’ll corrode the wire on that end, making e.g. copper chloride. With a carbon electrode and any chloride compound as the electrolyte, you’ll produce chlorine; without a chloride electrolyte, you will not produce chlorine at any voltage, or with any electrode. And if you make chlorine and check the volumes, you’ll find you always make one volume of chlorine for every volume of hydrogen. We imagine from this that the compounds are made of fixed atoms that transfer electrons in fixed whole numbers per molecule. You always make two volumes of hydrogen for every volume of oxygen because (we think) making oxygen requires twice as many electrons as making hydrogen.

At home electrolysis experiment

We get the same volume of chlorine as hydrogen because making chlorine and hydrogen requires the same amount of electrons to be transferred. These are the sort of experiments that caused people to believe in atoms and molecules as the fundamental unchanging components of matter. Different solutes, voltages, and electrodes will affect how fast you make hydrogen and oxygen, as will the amount of dissolved solute, but the gas produced are always the same, and the ratio of volumes is always proportional to the amperage in a fixed ratio of small whole numbers.

As always, don’t let significant quantities of use hydrogen and oxygen or pure hydrogen and chlorine mix in a closed space. Hydrogen and oxygen is quite explosive brown’s gas; hydrogen and chlorine are reactive as well. When working with chlorine it is best to work outside or near an open window: chlorine is a poison gas.

You may also want to try this with non-electrolytes, pure water or water with sugar or alcohol dissolved. You will find there is hardly any amperage or gas with these, but the small amount of gas produced will retain the same ratio. For college level folks, here is some physics/math relating to the minimum voltage and relating to the quantities you should expect at any amperage.

2) Now let’s try electro-plating metals. Using the right solutes, metals can be made to coat your electrodes the same way that bubbles of gas coated your electrodes in the experiments above. The key is to find the right chemical, and as a start let me suggest the copper sulphate sold in hardware stores to stop root growth. As an alternative copper sulphate is often sold as part of a fertilizer solution like “Miracle grow.” Look for copper on the label, or for a blue color fertilizer. Make a solution of copper using enough copper so that the solution is recognizably green, Use two steel washers as electrodes (that is connect the wires from your battery to the washers) and put them in the solution. You will find that one side turns red, as it is coated with copper. Depending on what else your copper solution contained, bubbles may appear at the other washer, or the other washer will corrode.

You are now ready to take this to a higher level — silver coating. take a piece of silver plated material that you want to coat, and clean it nicely with soap and water. Connect it to the electrode where you previously coated copper. Now clean out the solution carefully. Buy some silver nitrate from a drug store, and dissolve a few grams (1/8 tsp for a start) in pure water; place the silverware and the same electrodes as before, connected to the battery. For a nicer coat use a 1 1/2 volt lantern battery; the 6 V battery will work too, but the silver won’t look as nice. With silver nitrate, you’ll notice that one electrode produces gas (oxygen) and the other turns silvery. Now disconnect the silvery electrode. You can use this method to silver coat a ring, fork, or cup — anything you want to have silver coated. This process is called electroplating. As with hydrogen production, there is a proportional relationship between the time, the amperage and the amount of metal you deposit — until all the silver nitrate in solution is used up.

As a yet-more complex version, you can also electroplate without using a battery. This was my Simple electroplating (presented previously). Consider this only after you understand most everything else I’ve done. When I saw this the first time in high school I was confused.

3) Casting metal objects using melted pennies, heat from a gas stove, and sand or plaster as a cast. This is pretty easy, but sort of dangerous — you need parents help, if only as a watcher. This is a version of an experiment I did as a kid. I did metal casting using lead that some plumbers had left over. I melted it in a tin can on our gas stove and cast “quarters” in a plaster mold. Plumbers no longer use lead, but modern pennies are mostly zinc, and will melt about as well as my lead did. They are also much safer.

As a preparation for this experiment, get a bucket full of sand. This is where you’ll put your metal when you’re done. Now get some pennies (1970 or later), a pair of pliers, and an empty clean tin can, and a gas stove. If you like you can make a plaster mold of some small object: a ring, a 50 piece — anything you might want to cast from your pennies. With parents’ help, light your gas stove, put 5-8 pennies in the empty tin can, and hold the can over the lit gas burner using your pliers. Turn the gas to high. In a few minutes the bottom of the can will burn and become red-hot. About this point, the pennies will soften and melt into a silvery puddle. By tilting the can, you can stir the metal around (don’t get it on you!). When it looks completely melted you can pour the molten pennies into your sand bucket (carefully), or over your plaster mold (carefully). If you use a mold, you’ll get a zinc copy of whatever your mold was: jewelry, coins, etc. If you work at it, you’ll learn to make fancier and fancier casts. Adult help is welcome to avoid accidents. Once the metal solidifies, you can help cool it faster by dripping water on it from a faucet. Don’t touch it while it’s hot!

A plaster mold can be made by putting a 50¢ piece at the bottom of a paper cup, pouring plaster over the coin, and waiting for it to dry. Tear off the cup, turn the plaster over and pull out the coin; you’ve got a one-sided mold, good enough to make a one-sided coin. If you enjoy this, you can learn more about casting on Wikipedia; it’s an endeavor that only costs 4 or 5 cents per try. As a safety note: wear solid leather shoes and cover the floor near the stove with a board. If you drop the metal on the floor you’ll have a permanent burn mark on the floor and your mother will not be happy. If you drop hot metal on your you’ll have a permanent injury, and you won’t be happy. Older pennies are made of copper and will not melt. Here’s a video of someone pouring a lot of metal into an ant-hill (kills lots of ants, makes a mold of the hill).

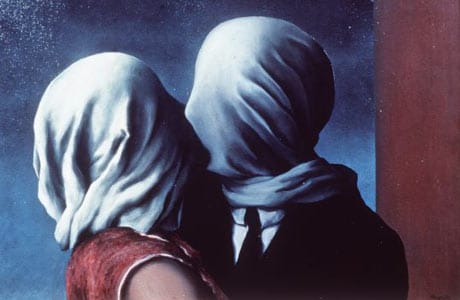

It’s nice to have assistants, friends and adult help in the laboratory when you do science. Even without the castle, it’s what Dr. Frankenstein did.

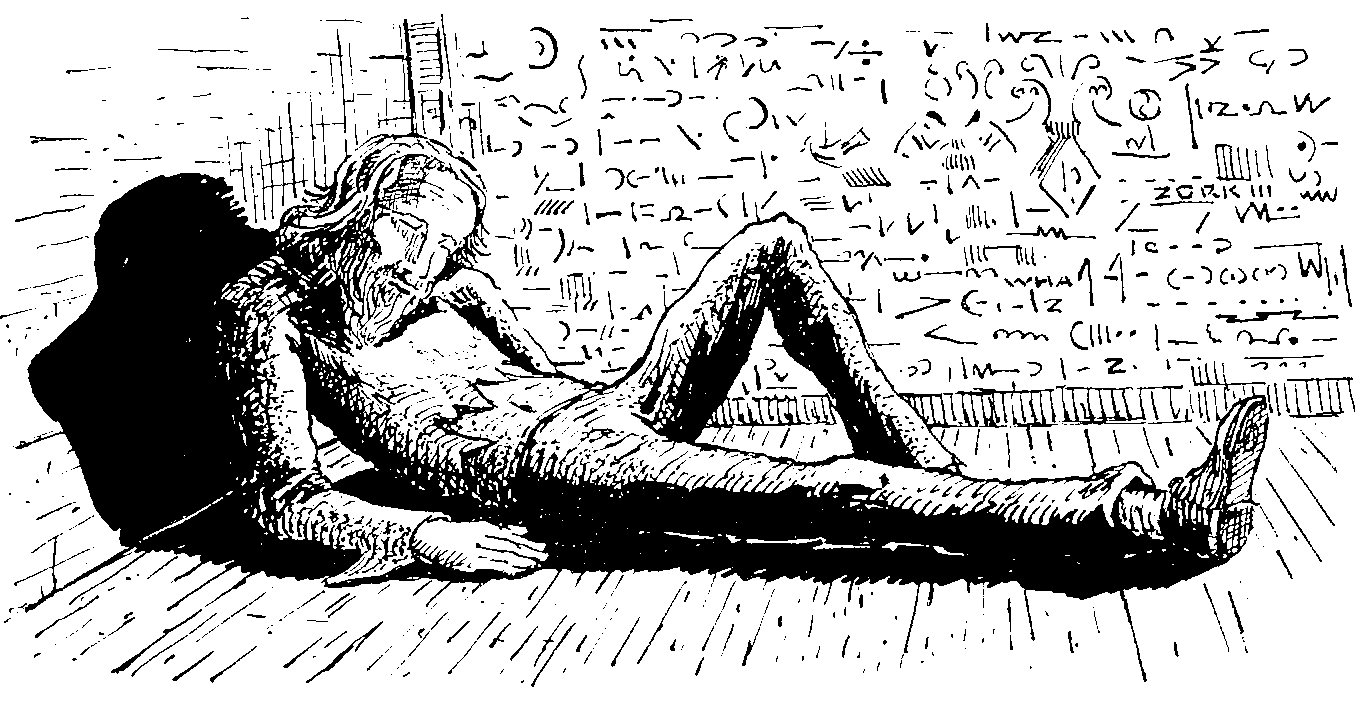

4) Bringing a dead frog back to life (sort of). Make a high voltage battery of 45 to 90 V battery by attaching 5-10, 9V batteries in a daisy chain they will snap together. If you touch both exposed contacts you’ll give yourself a wicked shock. If you touch the electrodes to a newly killed frog, the frog legs will kick. This is sort of groovy. It was the inspiration for Dr. Frankenstein (at right), who then decides he could bring a person back from the dead with “more power.” Frankenstein’s monster is brought back to life this way, but ends up killing the good doctor. Shocks are sometimes helpful reanimating people stricken by heat attacks, and many buildings have shockers for this purpose. But don’t try to bring back the long-dead. By all accounts, the results are less-than pleasing. Try dissecting the rest of the frog and guess what each part is (a world book encyclopedia helps). As I recall, the heart keeps going for a while after it’s out of the frog — spooky.

5) Another version of this shocker is made with a small transformer (1″ square, say, radioshack) and a small battery (1.5-6V). Don’t use the 90V battery, you’ll kill someone. As a first version of this shocker, strip 1″ of insulation off of the ends of some wire 12″ long say, and attach one end to two paired wires of the transformer (there will usually be a diagram in the box). If the transformer already has some wires coming out, all you have to do is strip more insulation off the ends so 1″ is un-inuslated. Take two paired ends in your hand, holding onto the uninsulated part and touch both to the battery for a second or two. Then disconnect them while holding the bare wires; you’ll get a shock. As a nastier version, get a friend to hope the opposite pair of wires on the uninsulated parts, while you hold the insulated parts of your two. Touch your two to the battery and disconnect while holding the insulation, you will see a nice spark, and your friend will get a nice shock. Play with it; different arrangements give more sparks or bigger shocks. Another thing you can do: put your experiment near a radio or TV. The transformer sparks will interfere with most nearby electronics; you can really mess up a computer this way, so keep it far from your computer. This is how wireless radio worked long ago, and how modern warfare will probably go. The atom bomb was detonated with a spark like this.

If you want to do more advanced science, it’s a good idea to learn math. This is important for statistics, for engineering, for quantum mechanics, and can even help for music. Get a few good high school or college books and read them cover to cover. An approach to science is to try to make something cool, that sort-of works, and then try to improve it. You then decide what a better version would work like, modify your original semi-randomly and see if you’re going in the right direction. Don’t redesign with only one approach –it may not work. Read whatever you can, but don’t believe all you read. Often books are misleading, or wrong, and blogs are worse (I ought to know). When you find mistakes, note them in the margin, and try to explain them. You may find you were right, or that the book was right, but it’s a learning experience. If you like you can write the author and inform him/her of the errors. I find mailed letters are more respectful than e-mails — it shows you put in more effort.

Robert Buxbaum, February 20, 2014. Here’s the difference between metals and non-metals, and a periodic table cup that I made, and sell. And here’s a difference between science and religion – reproducibility.

Like this:

Like Loading...