Innovation is the special sauce that propels growth and allows a country to lead and prosper. The current Nobel prize believe that innovation powered the Industrial Revolution, causing England to become rich and powerful, while other nations remained poor, weak, and stagnant. Similarly, Innovation, they believe is why 19th century Japan rose to defeat China, and propelled China’s 21st century rise. But why did they succeed when others did not. What could the leader of a country do to bring power and wealth through innovation. Improved education seems to help; all of the innovation countries have it, but it is not the whole. Some educated countries (Germany, Russia) stagnate. An open economy is nice, but it isn’t sufficient or that necessary: (look at China). That was the topic of this year’s, 2025 Nobel prize in economics to Mokyr, Howitt, and Aghion, with half going to Joel Mokyr for his insights, historical and forward looking, the other half going for economic modeling. I give below my understanding of their insights, more technical than most, but not so mathematical as to be obtuse the normal reader..

The winners hold that innovation, as during the industrial revolution, is a non-continuous contribultion caused by a particular combination of education and market opportunity, of theoretical knowledge, and practical, and that a key aspect is depreciation (destruction) of other suppliers. Let’s start by creating a simple, continuous function model for economic growth where growth = capital growth, that is dK/dt. K, Capital, is understood to be the sum of money, equipment, and labor knowledge, and t is time with dK/dt, the change in K with time modeled as equal to the savings rate, s, times economic activity, Y minus a depreciation factor, δ, times capital, K.

growth = dK/dt = sY − δ K.

For the authors, Y = GDP + x, where x is the cost of outside goods used. They then claim that Y is a non-linear function of K, where K is now considered a product of capital goods and labor K = xL and,

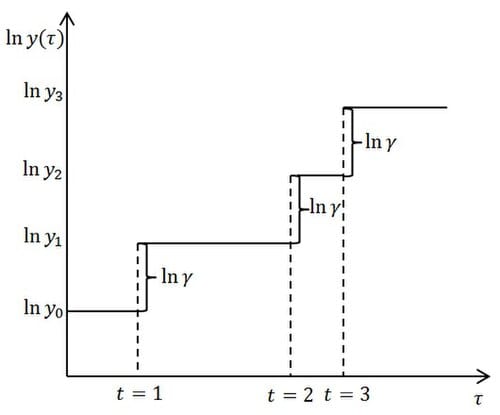

dY/dK = AKα + γ where 0< α <1, and where γ is the contribution of innovation and/or depreciation. The power function, as I understand it, is a mathematical way of saying there are economies of scale. The authors assume a set of interacting enterprises (countries0 so that the innovation factor, γ for one country is the depreciation factor for the other. That is, growth and destruction are connected, with growth being a function of monopoly power — control of your innovation.

According to the Nobel winners, γ is built n previous γ as shown in the digram at right. It can not be predicted as such, but requires education and monopolistic power. The inventor-manufacturer of the typewriter has a monopolistic advantage over the makers of fountain pens. Innovation thus causes depreciation, δ K as one new innovation depreciates many old processes and products. If you add enough math, you can derive formulas for GDP and GDP growth, all based on factors like A and α, that are hard to measure.

GDP = α(2α/1−α) (1-α2)A L,

Thus, GDP is proportional to Labor, L and per-capita GDP is mostly an independent function related to economies of scale and the ability to use capital and labor which is related to general country-wide culture.

The above analysis, as I understand it, is in contrast to Kensyan models, where growth is unrelated to innovation, and where destruction is bad. In these Kenysean models, growth can be created by government spending, especial spending to maintain large industries with economies of scale and by spending to promote higher education. The culture preferred here, as I understand is one that rewards risk-taking, monopoly economics, and creative destruction. Howitt, and Aghion, importantly codify all this with formulas, as presented above that (to me) provide little specific. No great guidance to the head of a country. Nor does the math make the models more true, but it makes the statements somewhat clearer. Or perhaps the only real value of the math is to make things sound more scientific see the Tom Lehrer song, Sociology.

This work seems more realistic, to me, than the Keynesian models Both models are mathematically consistent, but if Keynes’s were true, Britain might still be on top, and Zambia would be a close competitor among the richest countries on earth. Besides these new fellows seem to agree with the views of Peter Cooper, my hero. See more here.

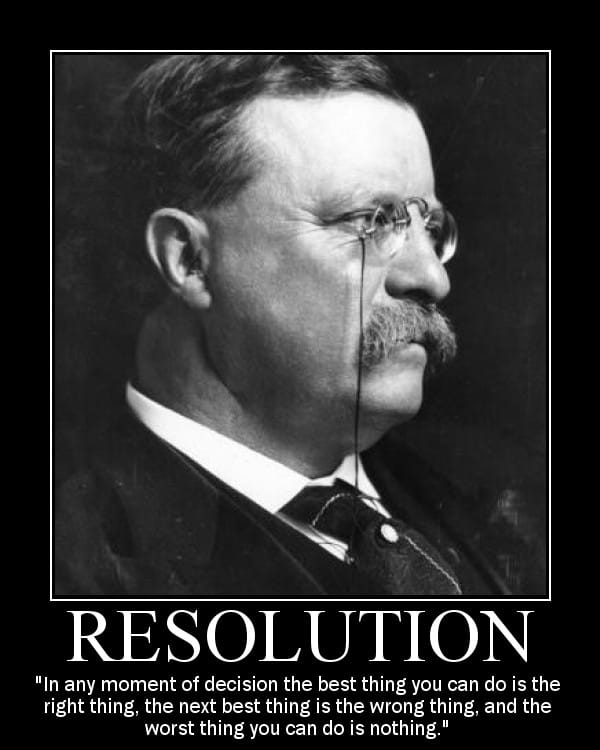

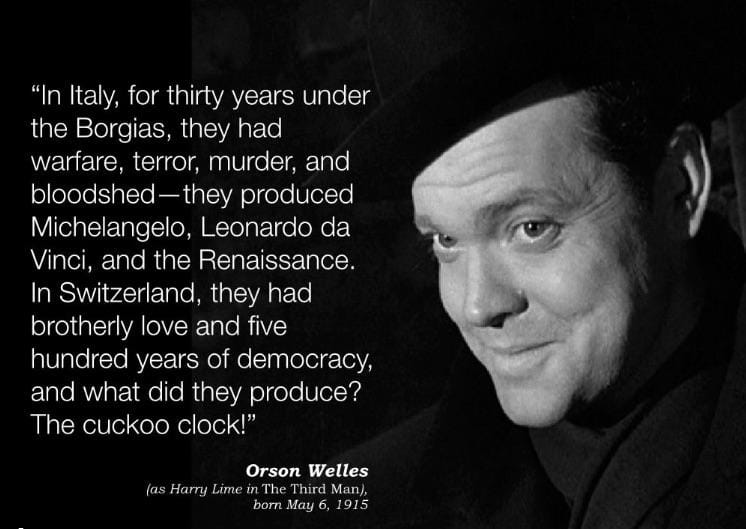

Writing all this reminds me that the fundamental assumption that progress is good, in not necessarily true. I quote above a line that Orson Wells, as Harry Lime, ad-libbed for the movie, “The Third Man.” Lime points out that innovation goes with suffering, and claims that Switzerland had little innovation because of its stability. Perhaps then, what you really want is the stability and peace of Switzerland, along with the lack of domination and innovation. On the same note, I’ve noticed that engineering innovators often ruin themselves dining in ruin, while the peaceable, stable civil engineers live long pleasant lives of honor.

Robert Buxbaum, November 16, 2025. A note about Switzerland is that was peaceful and stable because of a strong military. As Publius Vegetius wrote, Si vis pachim para bellum (if you wish of peace, prepare for war).