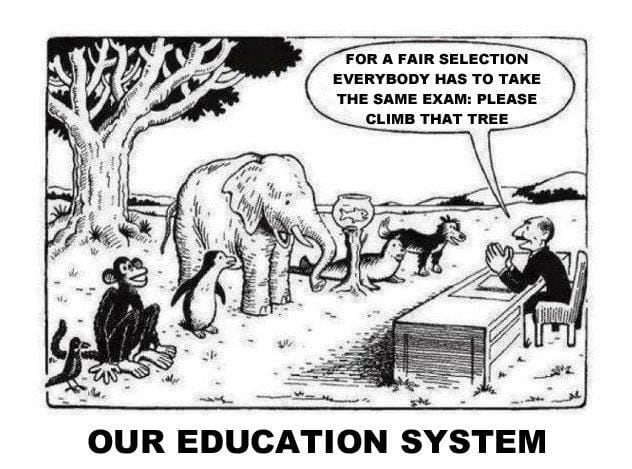

A linchpin of middle school and high-school education is teaching ‘the scientific method.’ This is the method, students are led to believe, that scientists use to determine Truths, facts, and laws of nature. Scientists, students are told, start with a hypothesis of how things work or should work, they then devise a set of predictions based on deductive reasoning from these hypotheses, and perform some critical experiments to test the hypothesis and determine if it is true (experimentum crucis in Latin). Sorry to say, this is a path to error, and not the method that scientists use. The real method involves a few more steps, and follows a different order and path. It instead follows the path that Sherlock Holmes uses to crack a case.

The actual method of Holmes, and of science, is to avoid beginning with a hypothesis. Isaac Newton claimed: “I never make hypotheses” Instead as best we can tell, Newton, like most scientists, first gathered as much experimental evidence on a subject as possible before trying to concoct any explanation. As Holmes says (Study in Scarlet): “It is a capital mistake to theorize before you have all the evidence. It biases the judgment.”

Holmes barely tolerates those who hypothesize before they have all the data: “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.” (Scandal in Bohemia).

Then there is the goal of science. It is not the goal of science to confirm some theory, model, or hypothesis; every theory probably has some limited area where it’s true. The goal for any real-life scientific investigation is the desire to explain something specific and out of the ordinary, or do something cool. Similarly, with Sherlock Holmes, the start of the investigation is the arrival of a client with a specific, unusual need – one that seems a bit outside of the normal routine. Similarly, the scientist wants to do something: build a bigger bridge, understand global warming, or how DNA directs genetics; make better gunpowder, cure a disease, or Rule the World (mad scientists favor this). Once there is a fixed goal, it is the goal that should direct the next steps: it directs the collection of data, and focuses the mind on the wide variety of types of solution. As Holmes says: , “it’s wise to make one’s self aware of the potential existence of multiple hypotheses, so that one eventually may choose one that fits most or all of the facts as they become known.” It’s only when there is no goal, that any path will do.

In gathering experimental data (evidence), most scientists spend months in the less-fashionable sections of the library, looking at the experimental methods and observations of others, generally from many countries, collecting any scrap that seems reasonably related to the goal at hand. I used 3 x5″ cards to catalog this data and the references. From many books and articles, one extracts enough diversity of data to be able to look for patterns and to begin to apply inductive logic. “The little things are infinitely the most important” (Case of Identity). You have to look for patterns in the data you collect. Holmes does not explain how he looks for patterns, but this skill is innate in most people to a greater or lesser extent. A nice set approach to inductive logic is called the Baconian Method, it would be nice to see schools teach it. If the author is still alive, a scientist will try to contact him or her to clarify things. In every SH mystery, Holmes does the same and is always rewarded. There is always some key fact or observation that this turns up: key information unknown to the original client.

Based on the facts collected one begins to create the framework for a variety of mathematical models: mathematics is always involved, but these models should be pretty flexible. Often the result is a tree of related, mathematical models, each highlighting some different issue, process, or problem. One then may begin to prune the tree, trying to fit the known data (facts and numbers collected), into a mathematical picture of relevant parts of this tree. There usually won’t be quite enough for a full picture, but a fair amount of progress can usually be had with the application of statistics, calculus, physics, and chemistry. These are the key skills one learns in college, but usually the high-schooler and middle schooler has not learned them very well at all. If they’ve learned math and physics, they’ve not learned it in a way to apply it to something new, quite yet (it helps to read the accounts of real scientists here — e.g. The Double Helix by J. Watson).

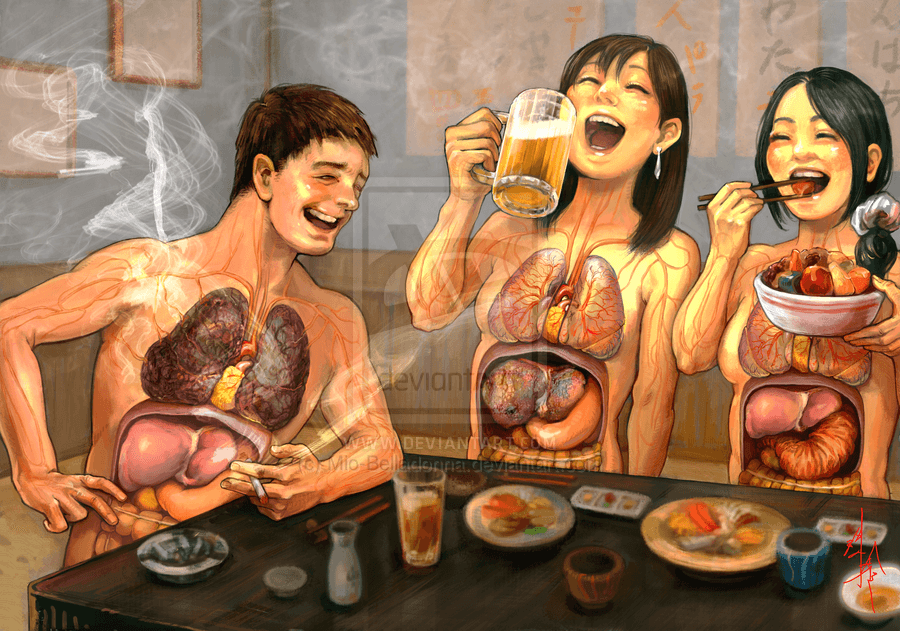

Usually one tries to do some experiments at this stage. Homes might visit a ship or test a poison, and a scientist might go off to his, equally-smelly laboratory. The experiments done there are rarely experimenti crucae where one can say they’ve determined the truth of a single hypothesis. Rather one wants to eliminated some hypotheses and collect data to be used to evaluate others. An answer generally requires that you have both a numerical expectation and that you’ve eliminated all reasonable explanations but one. As Holmes says often, e.g. Sign of the four, “when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth”. The middle part of a scientific investigation generally involves these practical experiments to prune the tree of possibilities and determine the coefficients of relevant terms in the mathematical model: the weight or capacity of a bridge of a certain design, the likely effect of CO2 on global temperature, the dose response of a drug, or the temperature and burn rate of different gunpowder mixes. Though not mentioned by Holmes, it is critically important in science to aim for observations that have numbers attached.

The destruction of false aspects and models is a very important part of any study. Francis Bacon calls this act destruction of idols of the mind, and it includes many parts: destroying commonly held presuppositions, avoiding personal preferences, avoiding the tendency to see a closer relationship than can be justified, etc.

In science, one eliminates the impossible through the use of numbers and math, generally based on your laboratory observations. When you attempt to the numbers associated with our observations to the various possible models some will take the data well, some poorly; and some twill not fit the data at all. Apply the deductive reasoning that is taught in schools: logical, Boolean, step by step; if some aspect of a model does not fit, it is likely the model is wrong. If we have shown that all men are mortal, and we are comfortable that Socrates is a man, then it is far better to conclude that Socrates is mortal than to conclude that all men but Socrates is mortal (Occam’s razor). This is the sort of reasoning that computers are really good at (better than humans, actually). It all rests on the inductive pattern searches similarities and differences — that we started with, and very often we find we are missing a piece, e.g. we still need to determine that all men are indeed mortal, or that Socrates is a man. It’s back to the lab; this is why PhDs often take 5-6 years, and not the 3-4 that one hopes for at the start.

More often than not we find we have a theory or two (or three), but not quite all the pieces in place to get to our goal (whatever that was), but at least there’s a clearer path, and often more than one. Since science is goal oriented, we’re likely to find a more efficient than we fist thought. E.g. instead of proving that all men are mortal, show it to be true of Greek men, that is for all two-legged, fairly hairless beings who speak Greek. All we must show is that few Greeks live beyond 130 years, and that Socrates is one of them.

Putting numerical values on the mathematical relationship is a critical step in all science, as is the use of models — mathematical and otherwise. The path to measure the life expectancy of Greeks will generally involve looking at a sample population. A scientist calls this a model. He will analyze this model using statistical model of average and standard deviation and will derive his or her conclusions from there. It is only now that you have a hypothesis, but it’s still based on a model. In health experiments the model is typically a sample of animals (experiments on people are often illegal and take too long). For bridge experiments one uses small wood or metal models; and for chemical experiments, one uses small samples. Numbers and ratios are the key to making these models relevant in the real world. A hypothesis of this sort, backed by numbers is publishable, and is as far as you can go when dealing with the past (e.g. why Germany lost WW2, or why the dinosaurs died off) but the gold-standard of science is predictability. Thus, while we a confident that Socrates is definitely mortal, we’re not 100% certain that global warming is real — in fact, it seems to have stopped though CO2 levels are rising. To be 100% sure you’re right about global warming we have to make predictions, e.g. that the temperature will have risen 7 degrees in the last 14 years (it has not), or Al Gore’s prediction that the sea will rise 8 meters by 2106 (this seems unlikely at the current time). This is not to blame the scientists whose predictions don’t pan out, “We balance probabilities and choose the most likely. It is the scientific use of the imagination” (Hound of the Baskervilles). The hope is that everything matches; but sometimes we must look for an alternative; that’s happened rarely in my research, but it’s happened.

You are now at the conclusion of the scientific process. In fiction, this is where the criminal is led away in chains (or not, as with “The Woman,” “The Adventure of the Yellow Face,” or of “The Blue Carbuncle” where Holmes lets the criminal free — “It’s Christmas”). For most research the conclusion includes writing a good research paper “Nothing clears up a case so much as stating it to another person”(Memoirs). For a PhD, this is followed by the search for a good job. For a commercial researcher, it’s a new product or product improvement. For the mad scientist, that conclusion is the goal: taking over the world and enslaving the population (or not; typically the scientist is thwarted by some detail!). But for the professor or professional research scientist, the goal is never quite reached; it’s a stepping stone to a grant application to do further work, and from there to tenure. In the case of the Socrates mortality work, the scientist might ask for money to go from country to country, measuring life-spans to demonstrate that all philosophers are mortal. This isn’t as pointless and self-serving as it seems, Follow-up work is easier than the first work since you’ve already got half of it done, and you sometimes find something interesting, e.g. about diet and life-span, or diseases, etc. I did some 70 papers when I was a professor, some on diet and lifespan.

One should avoid making some horrible bad logical conclusion at the end, by the way. It always seems to happen that the mad scientist is thwarted at the end; the greatest criminal masterminds are tripped by some last-minute flaw. Similarly the scientist must not make that last-mistep. “One should always look for a possible alternative, and provide against it” (Adventure of Black Peter). Just because you’ve demonstrated that iodine kills germs, and you know that germs cause disease, please don’t conclude that drinking iodine will cure your disease. That’s the sort of science mistakes that were common in the middle ages, and show up far too often today. In the last steps, as in the first, follow the inductive and quantitative methods of Paracelsus to the end: look for numbers, (not a Holmes quote) check how quantity and location affects things. In the case of antiseptics, Paracelsus noticed that only external cleaning helped and that the help was dose sensitive.

As an example in the 20th century, don’t just conclude that, because bullets kill, removing the bullets is a good idea. It is likely that the trauma and infection of removing the bullet is what killed Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley. Theodore Roosevelt was shot too, but decided to leave his bullet where it was, noticing that many shot animals and soldiers lived for years with bullets in them; and Roosevelt lived for 8 more years. Don’t make these last-minute missteps: though it’s logical to think that removing guns will reduce crime, the evidence does not support that. Don’t let a leap of bad deduction at the end ruin a line of good science. “A few flies make the ointment rancid,” said Solomon. Here’s how to do statistics on data that’s taken randomly.

Dr. Robert E. Buxbaum, scientist and Holmes fan wrote this, Sept 2, 2013. My thanks to Lou Manzione, a friend from college and grad school, who suggested I reread all of Holmes early in my PhD work, and to Wikiquote, a wonderful site where I found the Holmes quotes; the Solomon quote I knew, and the others I made up.

Like this:

Like Loading...