One evening at the Princeton grad college a younger fellow (an 18-year-old genius) asked the most simple, elegant question I had ever heard, one I’ve used ever since: “tell me”, he asked, “something that’s important and true.” My answer was that the entropy of the universe is always increasing. It’s a fundamentally important pattern, one I discovered to have a lot of applications and meaning. Let me explain the concept and why it’s true and useful. After that, why I find it’s meaningful.

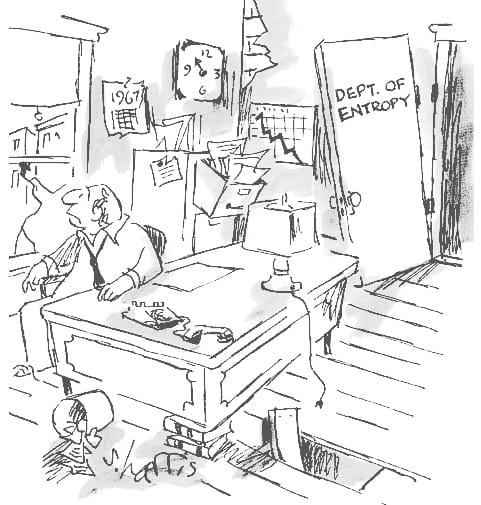

Famous entropy cartoon, Harris

The entropy of the universe is not something you can measure directly, but indirectly, from the availability of work in any corner of it. It’s related to randomness and the arrow of time. If you have, for example, an ice cube and a hot cup of water, you can get useful work from these by way of a thermocouple placed between them. You’ll get work until the two are at the same temperature. To get useful work out, you’ll have to add some other item.

Now, here’s how you can tell if time is moving forward: put an ice-cube into hot water, if the cube dissolves and the water becomes cooler, time is moving forward — or, at least it’s moving in the same direction as you are. If you can reach into a cup of warm water and pull out an ice-cube while making the water hot, time is moving backwards. — or rather, you are living backwards. Within any closed system, one where you don’t add things or energy (sunlight say), you can tell that time is moving forward because the forward progress of time always leads to the lack of availability of work. In the case above, you generated some electricity from the ice-cube and the hot water, but could not from the glass of warm water at the end.

You can not extract work from a heat source alone; to extract work some heat must be deposited in a cold sink. At best the entropy of the universe remains unchanged.

This observation is about as general and fundamental as any to understanding the world; it is the basis of the second law of thermodynamics: you can never extract useful work from a uniform temperature item, by making that item cooler say. To get useful work, you always need to make something else hotter, or colder, or you have to provide some chemical, altitude or other change that can not be reversed without adding more energy back. Thus, so long as time moves forward, everything “runs down” in terms of work availability.

The concept of entropy is the result of this observation along with another observation that energy is conserved. That is, if you want to heat some uniform substance, you must put in work and/or heat in any combination. And, if you want to cool something back to the original state, that same amount of heat + work must be taken out. In equation form, we say that, for any change, q +w is constant, where q is heat, and w is work. It’s the sum that’s constant, not the individual values so long as you count every 4.174 Joules of work as if it were 1 calorie of heat. If you input more heat, you have to add less work, and visa versa, but it’s always the same sum. When adding heat or work to the substance, we say that q or w is positive; when extracting heat or work, we say that q or w are negative quantities. So long as each 4.174 joules counts as if it were 1 calorie you get the same temperature change. This conservation of energy observation is called the first law of thermodynamics.

Now, since for every path between two states, q +w is the same, we say that q + w represents a path-independent quantity for the system, one we call internal energy, U where ∆U = q + w. This is a mathematical form of the first law of thermodynamics: you can’t take q + w out of nothing, or add it to something without making a change in the properties of the thing. The only way to leave things the same is if q + w = 0. We notice also that for any pure thing or uniform mixture undergoing a temperature change, the sum q +w that is needed to make that temperature change is proportional to the mass of the stuff. We can thus say that internal energy is an intensive quality. q + w = n ∆u where n is the grams of material, and ∆u is the change in internal energy per gram.

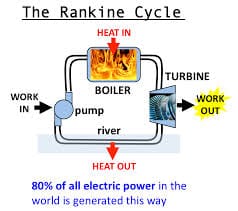

We are now ready to put the first and second laws together. We find we can extract work from a system if we take heat from a hot body (the hot water, say) and deliver some of it to something at a lower temperature (the ice-cube say). This can be done with a thermocouple, as above, or with a steam engine (Rankine cycle, shown above), or a Sterling engine, etc. These engines extract work only when there is a difference of temperatures. It’s is similar to a water wheel: a water wheel can extract work only when there is a flow of water from a high level to low; similarly in a heat engine, you only get work by taking heat energy from a hot heat-source and exhausting some of it to at a lower temperature. The remainder of that heat energy leaves the engine as work. That is, q1 -q2 = w. energy is always conserved. If you returned the amount of heat and work, you could return the hot source to its original condition. The second law isn’t violated either; there is no way you could run the engine without the cold sink. Accepting this as reasonable, we can now derive some very interesting, non-obvious truths.

We begin with the famous Carnot cycle. The Carnot cycle is an idealized heat engine with the interesting feature that it can be made to operate reversibly. That is, you can make it run forwards, taking a certain amount of work from a hot source, producing a certain amount of work and delivering a certain amount of heat to the cold sink; and you can run the same process backwards, as a refrigerator, taking in the same about of work and the same amount of heat from the cold sink and delivering the same amount to the hot source. Carnot showed by the following proof that all other reversible engines would have the same efficiency as his cycle and no engine, reversible or not, could be more efficient. The proof: if an engine could be designed that will extract a greater percentage of the heat as work when operating between a given hot source and cold sink it could be used to drive his Carnot cycle backwards. If the pair of engines were now combined so that the less efficient engine removed exactly as much heat from the sink as the more efficient engine deposited, the excess work produced by the more efficient engine would leave with no effect besides cooling the source. This combination would be in violation of the second law, something that we’d said was impossible.

Now let us try to understand the relationship that drives useful energy production. The ratio of heat in to heat out has got to be a function of the in and out temperatures alone. That is, q1/q2 = f(T1, T2). Similarly, q2/q1 = f(T2,T1) Now lets consider what happens when two Carnot cycles are placed in series between T1 and T2, with the middle temperature at Tm. For the first engine, q1/qm = f(T1, Tm), and similarly for the second engine qm/q2 = f(Tm, T2). Combining these we see that q1/q2 = (q1/qm)x(qm/q2) and therefore f(T1, T2) must always equal f(T1, Tm)x f(Tm/T2) =f(T1,Tm)/f(T2, Tm). In this relationship we see that the second term Tm is irrelevant; it is true for any Tm. We thus say that q1/q2 = T1/T2, and this is the limit of what you get at maximum (reversible) efficiency. You can now rearrange this to read q1/T1 = q2/T2 or to say that work, W = q1 – q2 = q2 (T1 – T2)/T2.

A strange result from this is that, since every process can be modeled as either a sum of Carnot engines, or of engines that are less-efficient, and since the Carnot engine will produce this same amount of reversible work when filled with any substance or combination of substances, we can say that this outcome: q1/T1 = q2/T2 is independent of path, and independent of substance so long as the process is reversible. We can thus say that for all substances there is a property of state, S such that the change in this property is ∆S = ∑q/T for all the heat in or out. In a more general sense, we can say, ∆S = ∫dq/T, where this state property, S is called the entropy. Since as before, the amount of heat needed is proportional to mass, we can say that S is an intensive property; S= n s where n is the mass of stuff, and s is the entropy change per mass.

Another strange result comes from the efficiency equation. Since, for any engine or process that is less efficient than the reversible one, we get less work out for the same amount of q1, we must have more heat rejected than q2. Thus, for an irreversible engine or process, q1-q2 < q2(T1-T2)/T2, and q2/T2 is greater than -q1/T1. As a result, the total change in entropy, S = q1/T1 + q2/T2 >0: the entropy of the universe always goes up or stays constant. It never goes down. Another final observation is that there must be a zero temperature that nothing can go below or both q1 and q2 could be positive and energy would not be conserved. Our observations of time and energy conservation leaves us to expect to find that there must be a minimum temperature, T = 0 that nothing can be colder than. We find this temperature at -273.15 °C. It is called absolute zero; nothing has ever been cooled to be colder than this, and now we see that, so long as time moves forward and energy is conserved, nothing will ever will be found colder.

Typically we either say that S is zero at absolute zero, or at room temperature.

We’re nearly there. We can define the entropy of the universe as the sum of the entropies of everything in it. From the above treatment of work cycles, we see that this total of entropy always goes up, never down. A fundamental fact of nature, and (in my world view) a fundamental view into how God views us and the universe. First, that the entropy of the universe goes up only, and not down (in our time-forward framework) suggests there is a creator for our universe — a source of negative entropy at the start of all things, or a reverser of time (it’s the same thing in our framework). Another observation, God likes entropy a lot, and that means randomness. It’s his working principle, it seems.

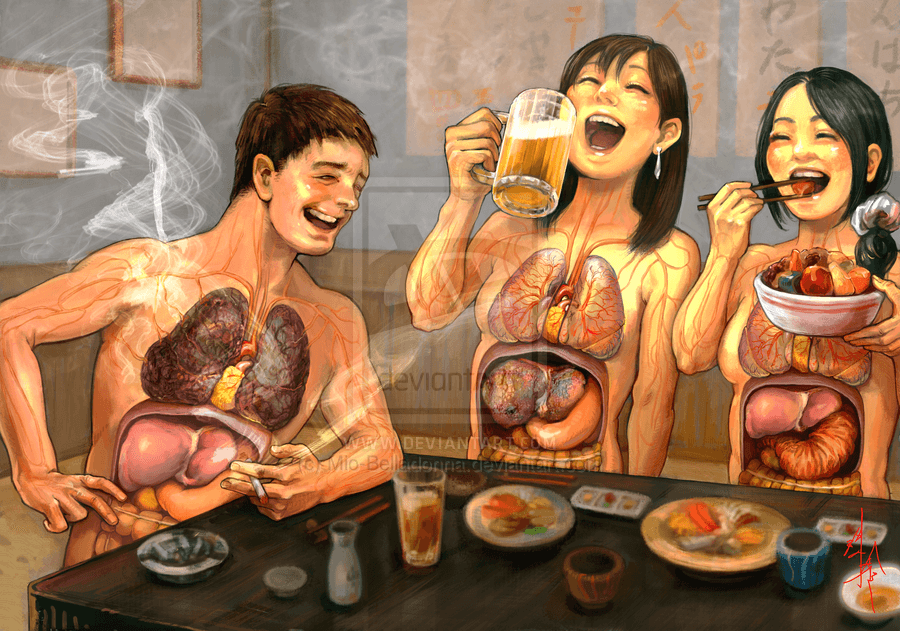

But before you take me now for a total libertine and say that since science shows that everything runs down the only moral take-home is to teach: “Let us eat and drink,”… “for tomorrow we die!” (Isaiah 22:13), I should note that his randomness only applies to the universe as a whole. The individual parts (planets, laboratories, beakers of coffee) does not maximize entropy, but leads to a minimization of available work, and this is different. You can show that the maximization of S, the entropy of the universe, does not lead to the maximization of s, the entropy per gram of your particular closed space but rather to the minimization of a related quantity µ, the free energy, or usable work per gram of your stuff. You can show that, for any closed system at constant temperature, µ = h -Ts where s is entropy per gram as before, and h is called enthalpy. h is basically the potential energy of the molecules; it is lowest at low temperature and high order. For a closed system we find there is a balance between s, something that increases with increased randomness, and h, something that decreases with increased randomness. Put water and air in a bottle, and you find that the water is mostly on the bottom of the bottle, the air is mostly on the top, and the amount of mixing in each phase is not the maximum disorder, but rather the one you’d calculate will minimize µ.

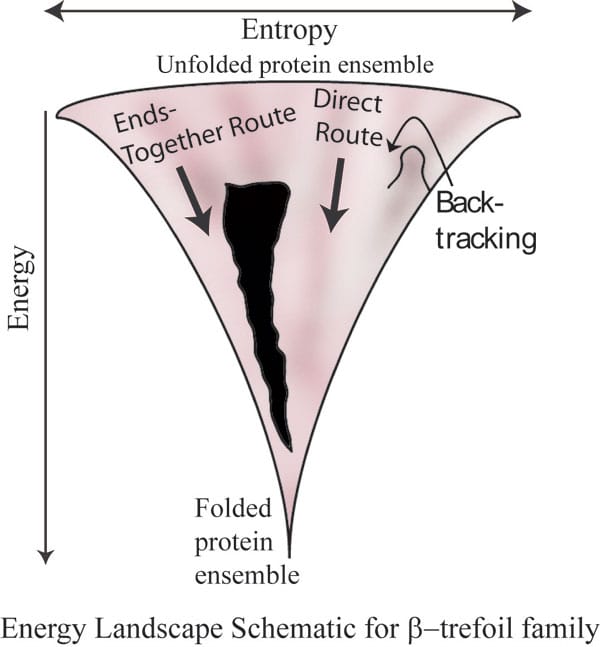

As a protein folds its randomness and entropy decrease, but its enthalpy decreases too; the net effect is one precise fold that minimizes µ.

This is the principle that God applies to everything, including us, I’d guess: a balance. Take protein folding; some patterns have big disorder, and high h; some have low disorder and very low h. The result is a temperature-dependent balance. If I were to take a moral imperative from this balance, I’d say it matches better with the sayings of Solomon the wise: “there is nothing better for a person under the sun than to eat, drink and be merry. Then joy will accompany them in their toil all the days of the life God has given them under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 8:15). There is toil here as well as pleasure; directed activity balanced against personal pleasures. This is the µ = h -Ts minimization where, perhaps, T is economic wealth. Thus, the richer a society, the less toil is ideal and the more freedom. Of necessity, poor societies are repressive.

Dr. Robert E. Buxbaum, Mar 18, 2014. My previous thermodynamic post concerned the thermodynamics of hydrogen production. It’s not clear that all matter goes forward in time, by the way; antimatter may go backwards, so it’s possible that anti matter apples may fall up. On microscopic scale, time becomes flexible so it seems you can make a time machine. Religious leaders tend to be anti-science, I’ve noticed, perhaps because scientific miracles can be done by anyone, available even those who think “wrong,” or say the wrong words. And that’s that, all being heard, do what’s right and enjoy life too: as important a pattern in life as you’ll find, I think. The relationship between free-energy and societal organization is from my thesis advisor, Dr. Ernest F. Johnson.

Like this:

Like Loading...