It’s a mistake, I think, to expect that comedy will be funny; the Devine comedy isn’t, nor are Shakespeare’s comedies. It seems, rather, that comedy is the result of mistakes, fakes, and drunks stumbling along to a (typically) unexpected outcome. That’s sometimes funny, as often not. Our expectation is that mistakes and fools will fail in whatever the try, but that’s hardly ever the outcome in literature. Or in life. As often as not, the idiot ends up as king with the intelligent man working for him. It’s as if God is a comic writer and we are his creation. Perhaps God keeps us around for our amusement value, and drops us when we get stale.

It’s not uncommon to have laughs in a comedy; a Shakespearian comedy has some, as does life. But my sense is that you find more jokes in a tragedy, e.g. Romeo and Juliet, or Julius Caesar. What makes these tragedies, as best I can tell, is the great number of honorable people behaving honorably. Unlike what Aristotle claims, tragedy doesn’t have to deal with particularly great people (Romeo and Juliet aren’t) but they must behave honorably. If Romeo were to say “Oh well, she’s dead, I’ll find another,” it would be a comedy. When the lovers choose honorable death over separation, that’s tragedy.

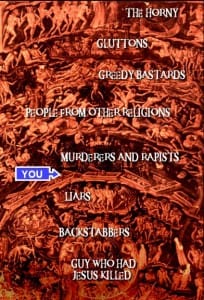

Dante’s hell viewed as a layer cake. The “you” label is where suicides end up; it’s from an anti-suicide blog.

Fortunately for us, in real life most people behave dishonorably most of the time, and the result is usually a happy ending. In literature and plays too, dishonorable behavior usually leads to a happy ending. In literature, I think it’s important for the happy ending to come about semi-naturally with some foreshadowing. God may protect fools, but He keeps to certain patterns, and I think a good comic writer should too. In one of my favorite musicals, the Music Man, the main character, a lovable con man is selling his non-teaching of music in an Iowa town. In the end, he escapes prison because, while the kids can’t play at all, the parents think they sound great. It’s one of the great Ah hah moments, I think. Similarly at the end of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado, it’s not really surprising that the king (Mikado) commutes the death sentence of his son’s friends on the thinnest of presence: he’s the king; those are his son’s friends, and one of them has married a horrible lady who’s been a thorn in the king’s side. Of course he commutes the sentence: he’s got no honor. And everyone lives happily.

Even in the Divine Comedy (Dante), the happy ending (salvation) comes about with a degree of foreshadowing. While you meet a lot of suffering fools in hell and purgatory, it’s not totally unexpected to find some fools and sinners in heaven too. Despite the statement at the entrance of hell, “give up all hope”, you expect and find there is Devine grace. It shows up in a sudden break-out from hell, where a horde of the damned are seen to fly past those in purgatory for being too pious. And you even find foolish sinning at the highest levels of heaven. The (prepared) happy ending is what makes it a good comedy, I imagine.

There is such a thing as a bad comedy, or a tragic-comedy. I suspect that “The merchant of Venice” is not a tragedy at all, but a poorly written, bad comedy. There are fools aplenty in merchant, but too many honorable folks as well. And the happy ending is too improbable: The disguised woman lawyer wins the case. The Jew loses his money and converts, everyone marries, and the missing ships reappear, as if by magic. A tragic-comedy, like Dr Horrible’s sing along blog; is something else. There are fools and mistakes, but not totally unexpected ending is unhappy. It happens in life too, but I prefer it when God writes it otherwise.

It seems to me that the battle of Bunker Hill was one of God’s comedies, or tragic-comedies depending on which side you look. Drunken Colonials build a bad fort on the wrong hill in the middle of the night. Four top British generals agree to attack the worthless fort with their best troops just to show them, and the result is the greatest British loss of life of the Revolutionary war — plus the British in charge of the worthless spit of land. It’s comic, despite the loss of life, and despite that these are not inferior people. There is a happy ending from the American perspective, but none from the British.

I can also imagine happy tragedies: tales where honorable people battle and produce a happy result. It happens rarely in life, and the only literature example I can think of is 1776 (the musical). You see the cream of the colonies, singing, dancing, and battling with each other with honorable commitment. And the result is a happy one, at least from the American perspective.

Robert E. Buxbaum, September 17-24, 2015. I borrowed some ideas here from Nietzsche: Human, All too Human, and Birth of Tragedy, and added some ideas of my own, e.g. re; God. Nietzsche is quite good on the arts, I find, but anti-good on moral issues (That’s my own, little Nietzsche joke, and my general sense). The original Nietzsche is rather hard to read, including insights like: “A joke is an epigram on the death of a feeling.”