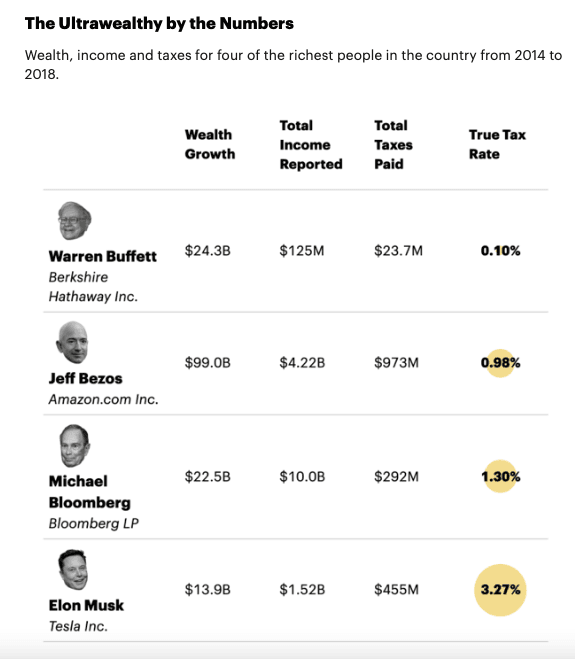

Two tax questions: (1) How do the top rich people manage to pay such low taxes, e.g. Warren Buffett paying at 0.1%. and (2) why do these rich folks campaign for higher taxes. Warren Buffett has campaigned for higher taxes for 50 years. These questions seem perhaps related.

I got my tax data from a public tax advocacy group, ProPublica. In 2021 they received the tax filings for many important people including the 25 US richest from the years 2014 to 2018. They find that these individuals paid a total of $13.6 billion in federal income tax while their wealth rose a collective $401 billion, go here for more. Dividing the numbers, we see an average income tax rate of only 3.4%, with Warren Buffett paying the least, 0.1%. This is far less than the “half of the rate that my secretary pays,” that Buffett likes to claim.

The reason these people pay so little tax is that their taxable income is zero. They use a very wide variety techniques to do this. Among these are charitable foundations, including those that lobby for higher taxes and against climate change. The foundations buy private planes and send the founders (and their families) to climate change events in the South of France or Davos, Switzerland. “Pro-tax” foundations hire tax accountants to research ways that the rich avoid taxes, often the founders then use these methods while speaking out against others who do the same. Bezos was so successful at avoiding income that he got welfare payments in two of the five years, ProPublica found. Soros and his son got $2,400 in COVID payments. They had almost no income. The one tax all these folks hate is tariffs because it is almost impossible to buy new, expensive things from abroad while avoiding them. See my essay, “Tariffs are inflationary, but not on you.”

Another advantage of a charitable foundation is that 74% of your donation can offset capital gains. You have to itemize your donations, but If you give $1 million to your foundation, you can use it to offset $740,000 of stock appreciation earnings. Not a bad deal. You can also use any stock losses against gains. Thus, it’s a good idea, if you itemize, to sell some losing stocks when you sell gainers (while holding on to other gainers, of course.) All of this is only available to those who itemize, and it’s only the rich who benefit by itemizing.

Borrowing money against your assets is another popular tax avoidance scheme, one that ordinary folks could use (but don’t over-do it*). The scheme is often called “Borrow, Buy, Die.” You borrow a large sum against your assets (your home, your stocks, or options –Musk has lots of Tesla options, etc). You then use the borrowed money to purchase property, typically: a vacation home, rental properties, a hotel, or a car. If you structure the purchase right, the interest can be deducted from any other earnings you have including rents. You then have no taxable income, or a lower income while the property appreciates. You can often structure the purchase so that depreciation can be deducted against income as well. Meanwhile, you get to drive the car, live at the vacation home, or rent it as an Air B&B, or stay at the hotel for free.

You live this way until you die. When you die, your heirs get the asset, but they are not taxed on the appreciation. The asset is transferred at its value at the time of death. You’ve avoided paying all the income tax you’d have to pay if you were to sell before death. Most home-owners do this on a small scale: They borrow to buy their home or the building where their business is. Or borrow to buy a vacation home or income property. They use through their life-time, deducting the interest, then leave it to their kids. There is no inheritance tax on most homes or small businesses, and the asset appreciates year to year. Both Nixon and Obama proposed eliminating this loophole by taxing appreciation at death. This would be a lot fairer than the current inheritance tax that is full of loopholes, and unfair when it works. If your parent bought a $10,000,000 item with taxable income, and it remains at that value, why should it be taxed a second time at death?

For a small businessman like me, it made sense to borrow to buy the building that my business operates out of and pay myself a normal rent. It’s income, as real as salary, but taxed at a lower rate, Besides there is no payroll tax on rental income. Another advantage of renting to myself is I can be trusted to fix the building and pay the rent, and I will not throw myself out if there is a downturn, nor will I raise the rents exorbitantly. My car is owned by my business, another plus. I pay a fee for personal use, but this is cheaper than using my own taxed income. When I die, the building (and car) will go to my heirs, tax free.

One last change I’d like to see is in the payroll tax. I’d like to see it tax the entire taxable income, but at a lower percent than the current 15.2 or 7.6. Currently the first $150,000 of income is payroll taxed at 15.2% for a self-employed individual, a plumber or office cleane, even before he/she pays income tax. An office worker is taxes at half this rate, 7.6% before income tax, with the company making up the other 7.6%. A CEO making $10 million pays this rate too, but only on the first $150,000. This amounts to $11,400 in payroll tax, or less than 0.11% of salary. I consider this disparity a bigger scandal than the fact that the richest 25 Americans paid only 3.4% in income tax.

Robert Buxbaum, November 25, 2025. *Trump presents a cautionary tale about property investing; if you invest at the wrong time, you can lose your shirt. In the late 80s, the property market in NY collapsed briefly, and he really was less than penniless. Don’t over-extend. The property market doesn’t collapse often, but you don’t want to be wiped out if it does.