Hydrogen fueled cars and buses are as clean to drive as battery vehicles and have better range and faster fueling times. Cost-wise, a hydrogen fuel tank is far cheaper and lighter than an equivalent battery and lasts far longer. Hydrogen is likely safer because the tanks do not carry their oxidant in them. And the price of hydrogen is relatively low, about that of gasoline on a per-mile basis: far lower than batteries when the cost of battery wear-out is included. Both Presidents Clinton and Bush preferred hydrogen over batteries, but the current administration favors batteries. Perhaps history will show them correct, but I think otherwise. Currently, there is not a hydrogen bus, car, or boat making runs at Disney’s Experimental Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT), nor is there an electric bus car or boat. I suspect it’s a mistake, at least convening the lack of a hydrogen vehicle.

The best hydrogen vehicles on the road have more range than the best electric vehicle, and fuel faster. The hydrogen powered, Honda Clarity debuted in 2008. It has a 270 mile range and takes 3-5 minutes to fuel with hydrogen at 350 atm, 5150 psi. By contrast, the Tesla S-sedan that debuted in 2012 claims only a 208 mile range for its standard, 60kWh configuration (the EPA claims: 190 miles) and requires three hours to charge using their fastest charger, 20 kW.

What limits the range of battery vehicles is that the stacks are very heavy and expensive. Despite using modern lithium-ion technology, Tesla’s 60 kWh battery weighs 1050 lbs including internal cooling, and adds another 250 lbs to the car for extra structural support. The Clarity fuel system weighs a lot less. The hydrogen cylinders weigh 150 lb and require a fuel cell stack (30 lb) and a smaller lithium-ion battery for start-up (90 lb). The net effect is that the Clarity weighs 3582 lbs vs 4647 lbs for the Tesla S. This extra weight of the Tesla seems to hurt its mileage by about 10%. The Tesla gets about 3.3 mi/kWh or 0.19 mile/lb of battery versus 60 miles/kg of hydrogen for the Clarity suggesting 3.6 mi/kWh at typical efficiencies.

High pressure hydrogen tanks are smaller than batteries and cheaper per unit range. The higher the pressure the smaller the tank. The current Clarity fuels with 350 atm, 5,150 psi hydrogen, and the next generation (shown below) will use higher pressure to save space. But even with 335 atm hydrogen (5000 psi) a Clarity could fuel a 270 mile range with four, 8″ diameter tanks (ID), 4′ long. I don’t know how Honda makes its hydrogen tanks, but suitable tanks might be made from 0.065″ Maranging (aged) stainless steel (UTS = 350,000 psi, density 8 g/cc), surrounded by 0.1″ of aramid fiber (UTS = 250,000 psi, density = 1.6 g/cc). With this construction, each tank would weigh 14.0 kg (30.5 lbs) empty, and hold 11,400 standard liters, 1.14 kg (2.5 lb) of hydrogen at pressure. These tanks could cost $1500 total; the 270 mile range is 40% more Than the Tesla S at about 1/10 the cost of current Tesla S batteries The current price of a replacement Tesla battery pack is $12,000, subsidized by DoE; without the subsidy, the likely price would be $40,000.

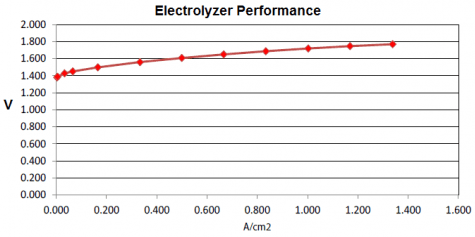

Currently hydrogen is more expensive than electricity per energy value, but my company has technology to make it cheaply and more cleanly than electricity. My company, REB Research makes hydrogen generators that produce ultra pure hydrogen by steam reforming wow alcohol in a membrane reactor. A standard generator, suitable to a small fueling station outputs 9.5 kg of hydrogen per day, consuming 69 gal of methanol-water. At 80¢/gal for methanol-water, and 12¢/kWh for electricity, the output hydrogen costs $2.50/kg. A car owner who drove 120,000 miles would spend $5,000 on hydrogen fuel. For that distance, a Tesla owner would spend only $4400 on electricity, but would have to spend another $12,000 to replace the battery. Tesla batteries have a 120,000 mile life, and the range decreases with age.

For a bus or truck at EPCOT, the advantages of hydrogen grow fast. A typical bus is expected to travel much further than 120,000 miles, and is expected to operate for 18 hour shifts in stop-go operation getting perhaps 1/4 the miles/kWh of a sedan. The charge time and range advantages of hydrogen build up fast. it’s common to build a hydrogen bus with five 20 foot x 8″ tanks. Fueled at 5000 psi., such buses will have a range of 420 miles between fill-ups, and a total tank weight and cost of about 600 lbs and $4000 respectively. By comparison, the range for an electric bus is unlikely to exceed 300 miles, and even this will require a 6000 lb., 360 kWh lithium-ion battery that takes 4.5 hours to charge assuming an 80 kW charger (200 Amps at 400 V for example). That’s excessive compared to 10-20 minutes for fueling with hydrogen.

While my hydrogen generators are not cheap: for the one above, about $500,000 including the cost of a compressor, the cost of an 80 kW DC is similar if you include the cost to run a 200 Amp, 400 V power line. Tesla has shown there are a lot of people who value clean, futuristic transport if that comes with comfort and style. A hydrogen car can meet that handily, and can provide the extra comforts of longer range and faster refueling.

Robert E. Buxbaum, February 12, 2014 (Lincoln’s birthday). Here’s an essay on Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, on the safety of batteries, and on battery cost vs hydrogen. My company, REB Research makes hydrogen generators and purifiers; we also consult.