For most people, there is a fundamental difference between solids and fluids. Solids have long-term permanence with no apparent diffusion; liquids diffuse and lack permanence. Put a penny on top of a dime, and 20 years later the two coins are as distinct as ever. Put a layer of colored water on top of plain water, and within a few minutes you’ll see that the coloring diffuse into the plain water, or (if you think the other way) you’ll see the plain water diffuse into the colored.

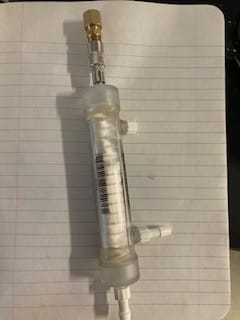

Now consider the transport of hydrogen in metals, the technology behind REB Research’s metallic membranes and getters. The metals are clearly solid, keeping their shapes and properties for centuries. Still, hydrogen flows into and through the metals at a rate of a light breeze, about 40 cm/minute. Another way of saying this is we transfer 30 to 50 cc/min of hydrogen through each cm2 of membrane at 200 psi and 400°C; divide the volume by the area, and you’ll see that the hydrogen really moves through the metal at a nice clip. It’s like a normal filter, but it’s 100% selective to hydrogen. No other gas goes through.

To explain why hydrogen passes through the solid metal membrane this way, we have to start talking about quantum behavior. It was the quantum behavior of hydrogen that first interested me in hydrogen, some 42 years ago. I used it to explain why water was wet. Below, you will find something a bit more mathematical, a quantum explanation of hydrogen motion in metals. At REB we recently put these ideas towards building a membrane system for concentration of heavy hydrogen isotopes. If you like what follows, you might want to look up my thesis. This is from my 3rd appendix.

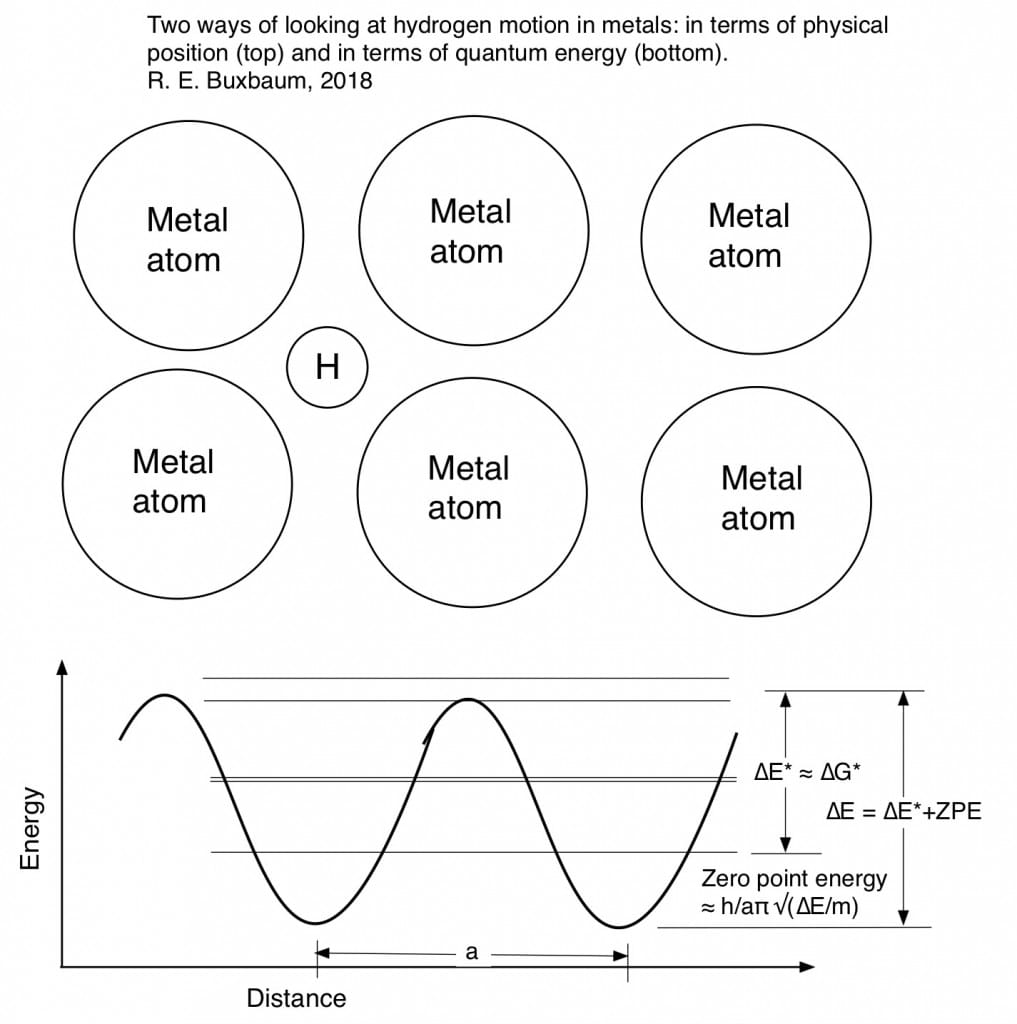

Although no-one quite understands why nature should work this way, it seems that nature works by quantum mechanics (and entropy). The basic idea of quantum mechanics you will know that confined atoms can only occupy specific, quantized energy levels as shown below. The energy difference between the lowest energy state and the next level is typically high. Thus, most of the hydrogen atoms in an atom will occupy only the lower state, the so-called zero-point-energy state.

A hydrogen atom, shown occupying an interstitial position between metal atoms (above), is also occupying quantum states (below). The lowest state, ZPE is above the bottom of the well. Higher energy states are degenerate: they appear in pairs. The rate of diffusive motion is related to ∆E* and this degeneracy.

The fraction occupying a higher energy state is calculated as c*/c = exp (-∆E*/RT). where ∆E* is the molar energy difference between the higher energy state and the ground state, R is the gas constant and T is temperature. When thinking about diffusion it is worthwhile to note that this energy is likely temperature dependent. Thus ∆E* = ∆G* = ∆H* – T∆S* where asterisk indicates the key energy level where diffusion takes place — the activated state. If ∆E* is mostly elastic strain energy, we can assume that ∆S* is related to the temperature dependence of the elastic strain.

Thus,

∆S* = -∆E*/Y dY/dT

where Y is the Young’s modulus of elasticity of the metal. For hydrogen diffusion in metals, I find that ∆S* is typically small, while it is often typically significant for the diffusion of other atoms: carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur…

The rate of diffusion is now calculated assuming a three-dimensional drunkards walk where the step lengths are constant = a. Rayleigh showed that, for a simple cubic lattice, this becomes:

D = a2/6τ

a is the distance between interstitial sites and t is the average time for crossing. For hydrogen in a BCC metal like niobium or iron, D=

a2/9τ; for a FCC metal, like palladium or copper, it’s

a2/3τ. A nice way to think about τ, is to note that it is only at high-energy can a hydrogen atom cross from one interstitial site to another, and as we noted most hydrogen atoms will be at lower energies. Thus,

τ = ω c*/c = ω exp (-∆E*/RT)

where ω is the approach frequency, or the amount of time it takes to go from the left interstitial position to the right one. When I was doing my PhD (and still likely today) the standard approach of physics writers was to use a classical formulation for this time-scale based on the average speed of the interstitial. Thus, ω = 1/2a√(kT/m), and

τ = 1/2a√(kT/m) exp (-∆E*/RT).

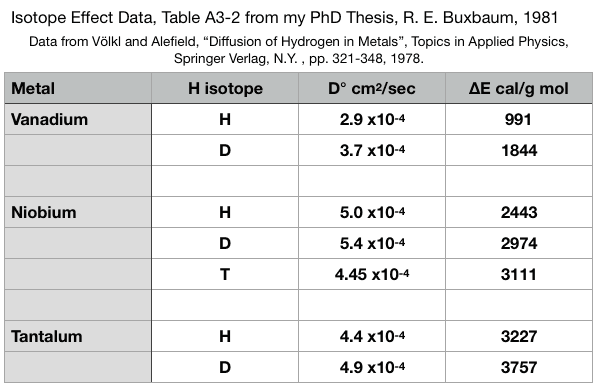

In the above, m is the mass of the hydrogen atom, 1.66 x 10-24 g for protium, and twice that for deuterium, etc., a is the distance between interstitial sites, measured in cm, T is temperature, Kelvin, and k is the Boltzmann constant, 1.38 x 10-16 erg/°K. This formulation correctly predicts that heavier isotopes will diffuse slower than light isotopes, but it predicts incorrectly that, at all temperatures, the diffusivity of deuterium is 1/√2 that for protium, and that the diffusivity of tritium is 1/√3 that of protium. It also suggests that the activation energy of diffusion will not depend on isotope mass. I noticed that neither of these predictions is borne out by experiment, and came to wonder if it would not be more correct to assume ω represent the motion of the lattice, breathing, and not the motion of a highly activated hydrogen atom breaking through an immobile lattice. This thought is borne out by experimental diffusion data where you describe hydrogen diffusion as D = D° exp (-∆E*/RT).

You’ll notice from the above that D° hardly changes with isotope mass, in complete contradiction to the above classical model. Also note that ∆E* is very isotope dependent. This too is in contradiction to the classical formulation above. Further, to the extent that D° does change with isotope mass, D° gets larger for heavier mass hydrogen isotopes. I assume that small difference is the entropy effect of ∆E* mentioned above. There is no simple square-root of mass behavior in contrast to most of the books we had in grad school.

As for why ∆E* varies with isotope mass, I found that I could get a decent explanation of my observations if I assumed that the isotope dependence arose from the zero point energy. Heavier isotopes of hydrogen will have lower zero-point energies, and thus ∆E* will be higher for heavier isotopes of hydrogen. This seems like a far better approach than the semi-classical one, where ∆E* is isotope independent.

I will now go a bit further than I did in my PhD thesis. I’ll make the general assumption that the energy well is sinusoidal, or rather that it consists of two parabolas one opposite the other. The ZPE is easily calculated for parabolic energy surfaces (harmonic oscillators). I find that ZPE = h/aπ √(∆E/m) where m is the mass of the particular hydrogen atom, h is Plank’s constant, 6.63 x 10-27 erg-sec, and ∆E is ∆E* + ZPE, the zero point energy. For my PhD thesis, I didn’t think to calculate ZPE and thus the isotope effect on the activation energy. I now see how I could have done it relatively easily e.g. by trial and error, and a quick estimate shows it would have worked nicely. Instead, for my PhD, Appendix 3, I only looked at D°, and found that the values of D° were consistent with the idea that ω is about 0.55 times the Debye frequency, ω ≈ .55 ωD. The slight tendency for D° to be larger for heavier isotopes was explained by the temperature dependence of the metal’s elasticity.

Two more comments based on the diagram I presented above. First, notice that there is middle split level of energies. This was an explanation I’d put forward for quantum tunneling atomic migration that some people had seen at energies below the activation energy. I don’t know if this observation was a reality or an optical illusion, but present I the energy picture so that you’ll have the beginnings of a description. The other thing I’d like to address is the question you may have had — why is there no zero-energy effect at the activated energy state. Such a zero energy difference would cancel the one at the ground state and leave you with no isotope effect on activation energy. The simple answer is that all the data showing the isotope effect on activation energy, table A3-2, was for BCC metals. BCC metals have an activation energy barrier, but it is not caused by physical squeezing between atoms, as for a FCC metal, but by a lack of electrons. In a BCC metal there is no physical squeezing, at the activated state so you’d expect to have no ZPE there. This is not be the case for FCC metals, like palladium, copper, or most stainless steels. For these metals there is a much smaller, on non-existent isotope effect on ∆E*.

Robert Buxbaum, June 21, 2018. I should probably try to answer the original question about solids and fluids, too: why solids appear solid, and fluids not. My answer has to do with quantum mechanics: Energies are quantized, and always have a ∆E* for motion. Solid materials are those where ω exp (-∆E*/RT) has unit of centuries. Thus, our ability to understand the world is based on the least understandable bit of physics.

Like this:

Like Loading...

is

is  and

and  can be understood as an attraction force between molecules and a molecular volume respectively. Alternately, they can be calculated from the

can be understood as an attraction force between molecules and a molecular volume respectively. Alternately, they can be calculated from the