Lincoln’s election was greeted with horror by the educated classes who considered him a western rube. “Honest Ape” he was called in the press. Horace Greeley couldn’t stand him, and blamed the civil war on his reckless speech. Continuing their view that the press is never wrong, Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, November 17, 1863 was given very poor reviews, see my essay on why.

But the press wasn’t all bitterness and gall. A two-hour speech earlier that day by Edward Everett, was a hit with those who’d travelled, some hundreds of miles to hear it. Everett’s showed he was educated and understood the dire situation and causes of the battle. And he presents the conflict in a classical context, as a continuation of Roman and Greek conflicts. Here follows the beginning and end of his two hour address.

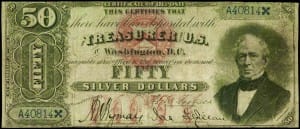

For nearly fifty years, Edward Everett’s face graced the Fifty dollar silver certificate. Now the world little notes, nor long remembers him. So passes glory.

[1] STANDING beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature. But the duty to which you have called me must be performed;–grant me, I pray you, your indulgence and your sympathy.

[2] It was appointed by law in Athens, that the obsequies of the citizens who fell in battle should be performed at the public expense, and in the most honorable manner. Their bones were carefully gathered up from the funeral pyre where their bodies were consumed, and brought home to the city. There, for three days before the interment, they lay in state, beneath tents of honor, to receive the votive offerings of friends and relatives,–flowers, weapons, precious ornaments, painted vases (wonders of art, which after two thousand years adorn the museums of modern Europe),–the last tributes of surviving affection. Ten coffins of funereal cypress received the honorable deposit, one for each of the tribes of the city, and an eleventh in memory of the unrecognized, but not therefore unhonored, dead, and of those whose remains could not be recovered. On the fourth day the mournful procession was formed: mothers, wives, sisters, daughters, led the way, and to them it was permitted by the simplicity of ancient manners to utter aloud their lamentations for the beloved and the lost; the male relatives and friends of the deceased followed; citizens and strangers closed the train. Thus marshalled, they moved to the place of interment in that famous Ceramicus, the most beautiful suburb of Athens, which had been adorned by Cimon, the son of Miltiades, with walks and fountains and columns,–whose groves were filled with altars, shrines, and temples,–whose gardens were kept forever green by the streams from the neighboring hills, and shaded with the trees sacred to Minerva and coeval with the foundation of the city,–whose circuit enclosed

“the olive grove of Academe,

Plato’s retirement, where the Attic bird

Trilled his thick-warbled note the summer long,”–

whose pathways gleamed with the monuments of the illustrious dead, the work of the most consummate masters that ever gave life to marble. There, beneath the overarching plane-trees, upon a lofty stage erected for the purpose, it was ordained that a funeral oration should be pronounced by some citizen of Athens, in the presence of the assembled multitude.

[3] Such were the tokens of respect required to be paid at Athens to the memory of those who had fallen in the cause of their country. For those alone who fell at Marathon a peculiar honor was reserved. As the battle fought upon that immortal field was distinguished from all others in Grecian history for its influence over the fortunes of Hellas,–as it depended upon the event of that day whether Greece should live, a glory and a light to all coming time, or should expire, like the meteor of a moment; so the honors awarded to its martyr-heroes were such as were bestowed by Athens on no other occasion. They alone of all her sons were entombed upon the spot which they had forever rendered famous. Their names were inscribed upon ten pillars erected upon the monumental tumulus which covered their ashes (where, after six hundred years, they were read by the traveller Pausanias), and although the columns, beneath the hand of time and barbaric violence, have long since disappeared, the venerable mound still marks the spot where they fought and fell,–

“That battle-field where Persia’s victim-horde

First bowed beneath the brunt of Hellas’ sword.”

[4] And shall I, fellow-citizens, who, after an interval of twenty-three centuries, a youthful pilgrim from the world unknown to ancient Greece, have wandered over that illustrious plain, ready to put off the shoes from off my feet, as one that stands on holy ground,–who have gazed with respectful emotion on the mound which still protects the dust of those who rolled back the tide of Persian invasion, and rescued the land of popular liberty, of letters, and of arts, from the ruthless foe,–stand unmoved over the graves of our dear brethren, who so lately, on three of those all-important days which decide a nation’s history,–days on whose issue it depended whether this august republican Union, founded by some of the wisest statesmen that ever lived, cemented with the blood of some of the purest patriots that ever died, should perish or endure,–rolled back the tide of an invasion, not less unprovoked, not less ruthless, than that which came to plant the dark banner of Asiatic despotism and slavery on the free soil of Greece? Heaven forbid! And could I prove so insensible to every prompting of patriotic duty and affection, not only would you, fellow-citizens, gathered many of you from distant States, who have come to take part in these pious offices of gratitude,–you, respected fathers, brethren, matrons, sisters, who surround me,–cry out for shame, but the forms of brave and patriotic men who fill these honored graves would heave with indignation beneath the sod.

[5] We have assembled, friends, fellow-citizens, at the invitation of the Executive of the great central State of Pennsylvania, seconded by the Governors of seventeen other loyal States of the Union, to pay the last tribute of respect to the brave men who, in the hard-fought battles of the first, second, and third days of July last, laid down their lives for the country on these hillsides and the plains before us, and whose remains have been gathered into the cemetery which we consecrate this day. As my eye ranges over the fields whose sods were so lately moistened by the blood of gallant and loyal men, I feel, as never before, how truly it was said of old that it is sweet and becoming to die for one’s country. I feel, as never before, how justly, from the dawn of history to the present time, men have paid the homage of their gratitude and admiration to the memory of those who nobly sacrifice their lives, that their fellow-men may live in safety and in honor. And if this tribute were ever due, to whom could it be more justly paid than to those whose last resting-place we this day commend to the blessing of Heaven and of men?

………………………………….. The speech went on for 58 sections of more-or-less this size and ends by mentioning the achievements of the other union armies and navy saying, “But they, I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country there will be no brighter page than that which relates THE BATTLES OF GETTYSBURG.”

_____________________________________________________________________

I find it long-winded and boring, but the crowd thought this speech wonderful. As grand as Lincoln’s 2 minute coda was plain. Part of the draw of Edward Everett was his cultured demeanor and his wide classical knowledge — a big contrast to Lincoln. Everett had been president of Harvard, and had been a senator, a congressman, governor of Massachusetts, Secretary of State, and US Ambassador to Great Britain. Lincoln had been a country lawyer and one-term congressman. When states started succeeding, Everett had been the one called on to negotiate a compromise that delayed war until the firing on fort Sumter. All impressive in the day, now mostly forgotten glories. Today, many of his lines ring hollow today, e.g. ” … that it is sweet and becoming to die for one’s country.” It just sounds weird to my ears. And the classic allusions sound pointless. By the early 20th century, most public pinion had changed; people decided that Lincoln’s was the better presentation, a monument to the spirit of man. The world remembers Lincoln fondly, but little notes, nor long remembers Everett, nor what he said there. The lesson: do not judge hastily. All things exist only in the context of time.

Robert E. Buxbaum, November 14, 2016. A week ago, Tuesday, our nation elected Donald Trump as 45th President of the United States, an individual as disliked and divisive as any since Lincoln. I do not know if he will prove to be honored or hated. There are demonstrations daily to remove him or overthrow the election. There are calls for succession, as when Lincoln took office. At Hampshire college, the flag was lowered in mourning. It’s possible that Trump is as offensive and unqualified as they say– but it is also possible that history will judge him otherwise in time. They did Lincoln.