There are two major green energy choices that people are considering to power small-to-medium size, mobile applications like cars and next generation, drone airplanes: rechargeable, lithium-ion batteries and hydrogen /fuel cells. Neither choice is an energy source as such, but rather a clean energy carrier. That is, batteries and fuel cells are ways to store and concentrate energy from other sources, like solar or nuclear plants for use on the mobile platform.

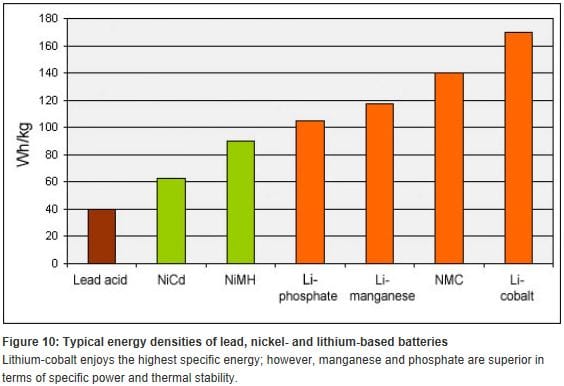

Of these two, rechargeable batteries are the more familiar: they are used in computers, cell phones, automobiles, and the ill-fated, Boeing Dreamliner. Fuel cells are less familiar but not totally new: they are used to power most submarines and spy-planes, and find public use in the occasional, ‘educational’ toy. Fuel cells provided electricity for the last 30 years of space missions, and continue to power the international space station when the station is in the dark of night (about half the time). Batteries have low energy density (energy per mass or volume) but charging them is cheap and easy. Home electricity costs about 12¢/kWhr and is available in every home and shop. A cheap transformer and rectifier is all you needed to turn the alternating current electricity into DC to recharge a battery virtually anywhere. If not for the cost and weight of the batteries, the time to charge the battery (usually and hour or two), batteries would be the obvious option.

Two obvious problems with batteries are the low speed of charge and the annoyance of having to change the battery every 500 charges or so. If one runs an EV battery 3/4 of the way down and charges it every week, the battery will last 8 years. Further, battery charging takes 1-2 hours. These numbers are acceptable if you use the car only occasionally, but they get more annoying the more you use the car. By contrast, the tanks used to hold gasoline or hydrogen fill in a matter of minutes and last for decades or many thousands of fill-cycles.

Another problem with batteries is range. The weight-energy density of batteries is about 1/20 that of gasoline and about 1/10 that of hydrogen, and this affects range. While gasoline stores about 2.5 kWhr/kg including the weight of the gas tank, current Li-Ion batteries store far less than this, about 0.15 kWhr/kg. The energy density of hydrogen gas is nearly that of gasoline when the efficiency effect is included. A 100 kg of hydrogen tank at 10,000 psi will hold 8 kg of hydrogen, or enough to travel about 350 miles in a fuel-cell car. This is about as far as a gasoline car goes carrying 60 kg of tank + gasoline. This seems acceptable for long range and short-range travel, while the travel range with eVs is more limited, and will likely remain that way, see below.

The volumetric energy density of compressed hydrogen/ fuel cell systems is higher than for any battery scenario. And hydrogen tanks are far cheaper than batteries. From Battery University. http://batteryuniversity.com/learn/article/will_the_fuel_cell_have_a_second_life

Cost is perhaps the least understood problem with batteries. While electricity is cheap (cheaper than gasoline) battery power is expensive because of the high cost and limited life of batteries. Lithium-Ion batteries cost about $2000/kWhr, and give an effective 500 charge/discharge cycles; their physical life can be extended by not fully charging them, but it’s the same 500 cycles. The effective cost of the battery is thus $4/kWhr (The battery university site calculates $24/kWhr, but that seems overly pessimistic). Combined with the cost of electricity, and the losses in charging, the net cost of Li-Ion battery power is about $4.18/kWhr, several times the price of gasoline, even including the low efficiency of gasoline engines.

Hydrogen prices are much lower than battery prices, and nearly as low as gasoline, when you add in the effect of the high efficiency fuel cell engine. Hydrogen can be made on-site and compressed to 10,000 psi for less cost than gasoline, and certainly less cost than battery power. If one makes hydrogen by electrolysis of water, the cost is approximately 24¢/kWhr including the cost of the electrolysis unit.While the hydrogen tank is more expensive than a gasoline tank, it is much cheaper than a battery because the technology is simpler. Fuel cells are expensive though, and only about 50% efficient. As a result, the as-used cost of electrolysis hydrogen in a fuel cell car is about 48¢/kWhr. That’s far cheaper than battery power, but still not cheap enough to encourage the sale of FC vehicles with the current technology.

My company, REB Research provides another option for hydrogen generation: The use of a membrane reactor to make it from cheap, easy to transport liquids like methanol. Our technology can be used to make hydrogen either at the station or on-board the car. The cost of hydrogen made this way is far cheaper than from electrolysis because most of the energy comes from the methanol, and this energy is cheaper than electricity.

In our membrane reactors methanol-water (65-75% Methanol), is compressed to 350 psi, heated to 350°C, and reacted to produce hydrogen that is purified as it is made. CH3OH + H2O –> 3H2 + CO2, with the hydrogen extracted through a membrane within the reactor.

The hydrogen can be compressed to 10,000 psi and stored in a tank on board an automobile or airplane, or one can choose to run this process on-board the vehicle and generate it from liquid fuel as-needed. On-board generation provides a saving of weight, cost, and safety since you can carry methanol-water easily in a cheap tank at low pressure. The energy density of methanol-water is about 1/2 that of gasoline, but the fuel cell is about twice as efficient as a gasoline engine making the overall volumetric energy density about the same. Not including the fuel cell, the cost of energy made this way is somewhat lower than the cost of gasoline, about 25¢/kWhr; since methanol is cheaper than gasoline on a per-energy basis. Methanol is made from natural gas, coal, or trees — non-imported, low cost sources. And, best yet, trees are renewable.

Like this:

Like Loading...