The Christmas Carol tells a tale that, for all the magic and fantasy, presents as true an economic picture of a man and his times as any in real-life history. Scrooge is a miserable character at the beginning of the tale, he lives alone in a dark house, without a wife or children, disliked by those around him. Scrooge has an office with a single employee (Bob Cratchit) in a tank-like office heated by a single lump of coal. He doesn’t associate much with friends or family, and one senses that he has few customers. He is poor by any life measure, and is likely poor relative to other bankers. At the end, through giving, he finds he enjoys life, is liked more, and (one has the sense) he may even get more business, and more money.

Scrooge (as best I can read him) believes in Malthus’s economic error of zero-sum wealth: That there is a limited amount of food, clothing, jobs, etc. and therefore Scrooge uses only the minimum, employs only the minimum, and spends only the minimum. Having more people would only mean more mouths to feed. As Scrooge says, “I can’t afford to make idle people merry. I help to support the establishments I have mentioned [the workhouses]. They cost enough, and … If they [the poor] would rather die,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

The teaching of the spirits is the opposite, and neither that of the Democrats or Republicans. Neither that a big government is needed to redistribute the wealth, nor that the free market will do everything. But, as I read it, the spirits bring a spiritual message of personal charity and happiness. That one enriches ones-self when one give of and by ones-self — just from the desire to be good and do good. The spirit of Christmas Present assures Scrooge that no famine will result from the excess population, but tells him of his 1800 brothers and shows him the unending cornucopia of food in the marketplace: spanish onions, oranges, fat chestnuts, grapes, and squab. Christmas future then shows him his funeral, and Tim’s: the dismal end of all men, rich and not: “Will you decide what men shall live, what men shall die? It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live.” And Scrooge reforms, learns: gives a smile and a laugh, and employs a young runner to get Cratchit a fat goose. He visits his nephew Fred, a cheerful businessman for dinner, and laughs while watching Tom Topper court Fred’s plump sister-in-law.

The spirits do not redistribute Scrooge’s wealth for him, and certainly don’t present a formula for how much to give whom. Instead they present a picture of the value of joy and societal fellowship (as I read it). The spirits help Scrooge out of his mental rut so he’s sees worthy endeavors everywhere. Both hoarding and redistribution are Malthusian-Scroogian messages, as I read them. Both are based on the idea that there is only so much that the world can provide.

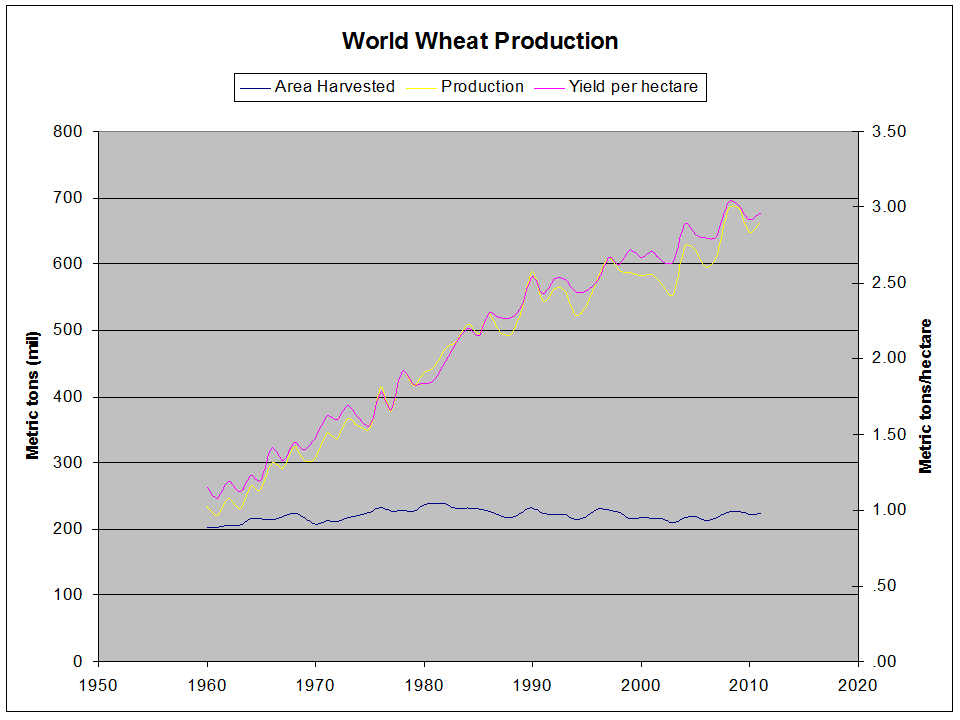

World wheat production tripled from 1960 to 2012 (faostat.fao.org), but acreage remained constant. More and more wheat from the same number of acres.

The history of food production suggests the spirits are right. The population is now three times what it was in Dickens’s day and mass starvation is not here. Instead we live among an “apoplectic opulence” of food. In a sense these are the product of new fertilizers, new tractors, and GMOs (Genetically modified organisms), but I would say it’s more the influence of better people. Plus, perhaps some extra CO2 in the air. Britons now complain about being too fat — and blame free markets for making them so. Over the last 50 years, wheat production has tripled, while the world population doubled, and the production of delicacies, like meat has expanded even faster. Unexpectedly, one sees that the opulence does not come from bringing new fields on-line — a process that would have to stop — but instead from increased production by the same tilled acres.

The opulence is not uniformly distributed, I should note. Countries that believe in Malthus and resort to hoarding or redistribution have been rewarded to see their grim prophesies fulfilled, as was Scrooge. Under Stalin, The Soviet Union redistributed grain from the unworthy farmer to the worth factory worker. The result was famine and Stalin felt vindicated by it. Even after Stalin, production never really grew under Soviet oversight, but remained at 75 Mtons/year from 1960 until the soviet collapse in 1990. Tellingly, nearly half of Soviet production was from the 3% of land under private cultivation. An unintended benefit: it appears the lack of Soviet grain was a major motivation for détente. England had famine problems too when they enacted Malthusian “corn acts” and when they prevented worker migration Irish ownership during the potato famine. They saw starvation again under Attlee’s managed redistribution. In the US, it’s possible that behaviors like FDR scattering the bonus army may have helped prolong the depression. My sense is that the modern-day Scrooges are those against immigration “the foreigners will take our jobs,” and those who oppose paying folks on time, or nuclear and coal for fear that we will warm the planet. Their vision of America-yet-to-be matches Scrooge’s: a one-man work-force in a tank office heated by a single piece of coal.

Now I must admit that I have no simple formula for the correct charity standard. How does a nation provide enough, but not so much that it removes motivation– and the joy of success. Perhaps all I can say is that there is a best path between hoarding and false generosity. Those pushing the extremes are not helping, but creating a Dickensian world of sadness and gloom. Rejoice with me then, and with the reformed Scrooge. God bless us all, each and every one.

Robert Buxbaum, January 7, 2015. Some ideas here from Jerry Bowyer in last year’s Forbes.