Built in 1931, the highest usable floor space of the Empire State building is 1250 feet (381m) above the ground. In 1973, that record was beaten by the World Trade Center building 1, 1,368 feet (417 m, building 2 was eight feet shorter). The Willis Tower followed 1974, and by 2004, the tallest building was the Taipei Tower, 1471 feet. Building heights had grown by 221 feet since 1931, and then the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, 2,426 ft ( 739.44m):. This is over 1000 feet taller than the new freedom tower, and nearly as much taller than the previous record holder. With the Saudi’s beginning work on a building even taller, it’s worthwhile asking how tall you could go, if your only limitations were ego and materials’ strength.

Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, Concrete + glass structure. Dubai tourism image.

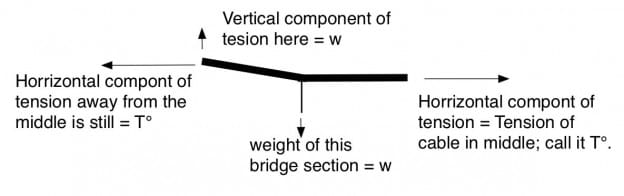

Having written about how long you could make a (steel) suspension bridge, the maximum height of a skyscraper seems like a logical next step. At first glance this would seem like a ridiculously easy calculation based on the math used to calculate the maximum length of a suspension bridge. As with the bridge, we’d make the structure from the strongest normal material: T1, low carbon, vanadium steel, and we’d determine the height by balancing this material’s yield strength, 100,000 psi (pounds per square inch), against its density, .2833 pounds per cubic inch.

If you balance these numbers, you calculate a height: 353,000 inches, 5.57 miles, but this is the maximum only for a certain structure, a wide flag-pole of T1 steel in the absent of wind. A more realistic height assumes a building where half the volume is empty space, used for living and otherwise, where 40% of the interior space contains vertical columns of T1 steel, and where there’s a significant amount of dead-weight from floors, windows, people, furniture, etc. Assume the dead weight is the equivalent of filling 10% of the volume with T1 steel that provides no structural support. The resulting building has an average density = (1/2 x 0.2833 pound/in3), and the average strength= (0.4 x 100,000 pound/in2). Dividing these numbers we get a maximum height, but only for a cylindrical building with no safety margin, and no allowance for wind.

H’max-cylinder = 0.4 x 100,000 pound/in2/ (.5 x 0.2833 pound/in3) = 282,400 inches = 23,532 ft = 4.46 miles.

This is more than ten times the Burj Khalifa, but it likely underestimates the maximum for a steel building, or even a concrete building because a cylinder is not the optimum shape for maximum height. If the towers were constructed conical or pyramidal, the height could be much greater: three times greater because the volume of a cone and thus its weight is 1/3 that of a cylinder for the same base and height. Using the same materials and assumptions,

The tallest building of Europe is the Shard; it’s a cone. The Eiffel tower, built in the 1800s, is taller.

H’max-cone = 3 H’max-cylinder = 13.37 miles.

A cone is a better shape for a very tall tower, and it is the shape chosen for “the shard”, the second tallest building in Europe, but it’s not the ideal shape. The ideal, as we’ll see, is something like the Eiffel tower.

Before speaking about this shape, I’d like to speak about building materials. At the heights we’re discussing, it becomes fairly ridiculous to talk about a steel and glass building. Tall steel buildings have serious vibration problems. Even at heights far before they are destroyed by wind and vibration , the people at the top will begin to feel quite sea-sick. Because of this, the tallest buildings have been constructed out of concrete and glass. Concrete is not practical for bridges since concrete is poor in tension, but concrete can be quite strong in compression, as I discussed here. And concrete is fire resistant, sound-deadening, and vibration dampening. It is also far cheaper than steel when you consider the ease of construction. The Trump Tower in New York and Chicago was the first major building here to be made this way. It, and it’s brother building in Chicago were considered aesthetic marvels until Trump became president. Since then, everything he’s done is ridiculed. Like the Trump tower, the Burj Khalifa is concrete and glass, and I’ll assume this construction from here on.

let’s choose to build out of high-silica, low aggregate, UHPC-3, the strongest concrete in normal construction use. It has a compressive strength of 135 MPa (about 19,500 psi). and a density of 2400 kg/m3 or about 0.0866 lb/in3. Its cost is around $600/m3 today (2019); this is about 4 times the cost of normal highway concrete, but it provides about 8 times the compressive strength. As with the steel building above, I will assume that, at every floor, half of the volume is living space; that 40% is support structure, UHPC-3, and that the other 10% is other dead weight, plumbing, glass, stairs, furniture, and people. Calculating in SI units,

H’max-cylinder-concrete = .4 x 135,000,000 Pa/(.5 x 2400 kg/m3 x 9.8 m/s2) = 4591 m = 2.85 miles.

The factor 9.8 m/s2 is necessary when using SI units to account for the acceleration of gravity; it converts convert kg-weights to Newtons. Pascals, by the way, are Newtons divided by square meters, as in this joke. We get the same answer with less difficulty using inches.

H’max-cylinder-concrete = .4 x 19,500 psi/(.5 x.0866 lb/in3) = 180,138″ = 15,012 ft = 2.84 miles

These maximum heights are not as great as for a steel construction, but there are a few advantages; the price per square foot is generally less. Also, you have fewer problems with noise, sway, and fire: all very important for a large building. The maximum height for a conical concrete building is three times that of a cylindrical building of the same design:

H’max–cone-concrete = 3 x H’max-cylinder-concrete = 3 x 2.84 miles = 8.53 miles.

Mount Everest, picture from the Encyclopedia Britannica, a stone cone, 5.5 miles high.

That this is a reasonable number can be seen from the height of Mount Everest. Everest is rough cone , 5.498 miles high. This is not much less than what we calculate above. To reach this height with a building that withstands winds, you have to make the base quite wide, as with Everest. In the absence of wind the base of the cone could be much narrower, but the maximum height would be the same, 8.53 miles, but a cone is not the optimal shape for a very tall building.

I will now calculate the optimal shape for a tall building in the absence of wind. I will start at the top, but I will aim for high rent space. I thus choose to make the top section 31 feet on a side, 1,000 ft2, or 100 m2. As before, I’ll make 50% of this area living space. Thus, each apartment provides 500 ft2 of living space. My reason for choosing this size is the sense that this is the smallest apartment you could sell for a high premium price. Assuming no wind, I can make this part of the building a rectangular cylinder, 2.84 miles tall, but this is just the upper tower. Below this, the building must widen at every floor to withstand the weight of the tower and the floors above. The necessary area increases for every increase in height as follows:

dA/dΗ = 1/σ dW/dH.

Here, A is the cross-sectional area of the building (square inches), H is height (inches), σ is the strength of the building material per area of building (0.4 x 19,500 as above), and dW/dH is the weight of building per inch of height. dW/dH equals A x (.5 x.0866 lb/in3), and

dA/dΗ = 1/ ( .4 x 19,500 psi) x A x (.5 x.0866 lb/in3).

dA/A = 5.55 x 10-6 dH,

∫dA/A = ∫5.55 x 10-6 dH,

ln (Abase/Atop) = 5.55 x 10-6 ∆H,

Here, (Abase/Atop) = Abase sq feet /1000, and ∆H is the height of the curvy part of the tower, the part between the ground and the 2.84 mile-tall, rectangular tower at the top.

Since there is no real limit to how big the base can be, there is hardly a limit to how tall the tower can be. Still, aesthetics place a limit, even in the absence of wind. It can be shown from the last equation above that stability requires that the area of the curved part of the tower has to double for every 1.98 miles of height: 1.98 miles = ln(2) /5.55 x 10-6 inches, but the rate of area expansion also keeps getting bigger as the tower gets heavier. I’m going to speculate that, because of artistic ego, no builder will want a tower that slants more than 45° at the ground level (the Eiffel tower slants at 51°). For the building above, it can be shown that this occurs when:

dA/dH = 4√Abase. But since

dA/dH = A 5.55 x 10-6 , we find that, at the base,

5.55 x 10-6 √Abase = 4.

At the base, the length of a building side is Lbase = √Abase= 4 /5.55 x 10-6 inches = 60060 ft = 11.4 miles. Artistic ego thus limits the area of the building to slightly over 11 miles wide of 129.4 square miles. This is about the area of Detroit. From the above, we calculate the additional height of the tower as

∆H = ln (Abase/Atop)/ 5.55 x 10-6 inches = 15.1/ 5.55 x 10-6 inches = 2,720,400 inches = 226,700 feet = 42.94 miles.

Hmax-concrete = 2.84 miles + ∆H = 45.78 miles. This is eight times the height of Everest, and while air pressure is pretty low at this altitude, it’s not so low that wind could be ignored. One of these days, I plan to show how you redo this calculation without the need for calculus, but with the inclusion of wind. I did the former here, for a bridge, and treated wind here. Anyone wishing to do this calculation for a basic maximum wind speed (100 mph?) will get a mention here.

From the above, it’s clear that our present buildings are nowhere near the maximum achievable, even for construction with normal materials. We should be able to make buildings several times the height of Everest. Such Buildings are worthy of Nimrod (Gen 10:10, etc.) for several reasons. Not only because of the lack of a safety factor, but because the height far exceeds that of the highest mountain. Also, as with Nimrod’s construction, there is a likely social problem. Let’s assume that floors are 16.5 feet apart (1 rod). The first 1.98 miles of tower will have 634 floors with each being about the size of Detroit. Lets then assume the population per floor will be about 1 million; the population of Detroit was about 2 million in 1950 (it’s 0.65 million today, a result of bad government). At this density, the first 1.98 miles will have a population of 634 million, about double that of the United States, and the rest of the tower will have the same population because the tower area contracts by half every 1.98 miles, and 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 … = 1.

Nimrod examining the tower, Peter Breugel

We thus expect the tower to hold 1.28 Billion people. With a population this size, the tower will develop different cultures, and will begin to speak different languages. They may well go to war too — a real problem in a confined space. I assume there is a moral in there somewhere, like that too much unity is not good. For what it’s worth, I even doubt the sanity of having a single government for 1.28 billion, even when spread out (e.g. China).

Robert Buxbaum, June 3, 2019.