Yesterday I blogged with a simple version of why the sky was blue and not green. Now I’d like to add mathematics to the treatment. The simple version said that the sky was blue because the sun color was a spectrum centered on yellow. I said that molecules of air scattered mostly the short wavelength, high frequency light colors, indigo and blue. This made the sky blue. I said that, the rest of the sunlight was not scattered, so that the sun looked yellow. I then said that the only way for the sky to be green would be if the sun were cooler, orange say, then the sky would be green. The answer is sort-of true, but only in a hand-waving way; so here’s the better treatment.

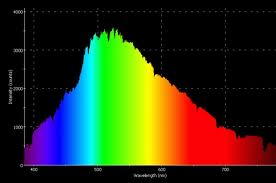

Light scatters off of dispersed small particles in proportion to wavelength to the inverse 4th power of the wavelength. That is to say, we expect air molecules will scatter more short wavelength, cool colors (purple and indigo) than warm colors (red and orange) but a real analysis must use the actual spectrum of sunlight, the light power (mW/m2.nm) at each wavelength.

The first thing you’ll notice is that the light from our sun isn’t quite yellow, but is mostly green. Clearly plants understand this, otherwise chlorophyl would be yellow. There are fairly large components of blue and red too, but my first correction to the previous treatment is that the yellow color we see as the sun is a trick of the eye called additive color. Our eyes combine the green and red of the sun’s light, and sees it as yellow. There are some nice classroom experiment you can do to show this, the simplest being to make a Maxwell top with green and red sections, spin the top, and notice that you see the color as yellow.

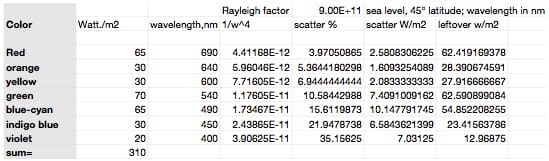

In order to add some math to the analysis of sky color, I show a table below where I divided the solar spectrum into the 7 representative colors with their effective power. There is some subjectivity to this, but I took red as the wavelengths from 620 to 750nm so I claim on the table was 680 nm. The average power of the red was 500 mW/m2nm, so I calculate the power as .5 W/m2nm x 130 nm = 65W/m2. Similarly, I took orange to be the 30W/m2 centered on 640nm, etc. This division is presented in the first 3 columns of the following table. The first line of the table is an approximate of the Rayleigh-scatter factor for our atmosphere, with scatter presented as the percent of the incident light. That is % scattered = 9E11/wavelength^4.

To use the Rayleigh factor, I calculate the 1/wavelength of each color to the 4th power; this is shown in the 4th column. The scatter % is now calculated and I apply this percent to the light intensities to calculate the amount of each color that I’d expect in the scattered and un-scattered light (the last two columns). Based on this, I find that the predominant wavelength in the color of the sky should be blue-cyan with significant components of green, indigo, and violet. When viewed through a spectroscope, I find that these are the colors I see (I have a pocket spectroscope and used it an hour ago to check). Viewed through the same spectroscope (with eye protection), I expect the sun should look like a combination of green and red, something our eyes see as yellow (I have not done this personally). At any rate, it appears that the sky looks blue because our eyes see the green+ cyan+ indigo + purple in the scattered light as sky blue.

At sunrise and sunset when the sun is on the horizon the scatter percents will be higher, so that all of the sun’s colors will be scattered except red and orange. The sun looks orange then, as expected, but the sky should look blue-green, as that’s the combination of all the other colors of sunlight when orange and red are removed. I’ve not checked this last yet. I’ll have to take my spectroscope to a fine sunset and see what I see when I look at the sky.