Here are six or so rocket science insights, some simple, some advanced. It’s a fun area of engineering that touches many areas of science and politics. Besides, some people seem to think I’m a rocket scientist.

A basic question I get asked by kids is how a rocket goes up. My answer is it does not go up. That’s mostly an illusion. The majority of the rocket — the fuel — goes down, and only the light shell goes up. People imagine they are seeing the rocket go up. Taken as a whole, fuel and shell, they both go down at 1 G: 9.8 m/s2, 32 ft/sec2.

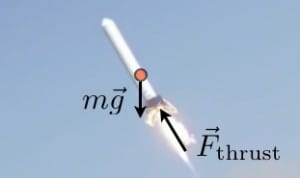

Because 1 G ofupward acceleration is always lost to gravity, you need more thrust from the rocket engine than the weight of rocket and fuel. This can be difficult at the beginning when the rocket is heaviest. If your engine provides less thrust than the weight of your rocket, your rocket sits on the launch pad, burning. If your thrust is merely twice the weight of the rocket, you waste half of your fuel doing nothing useful, just fighting gravity. The upward acceleration you’ll see, a = F/m -1G where F is the force of the engine, and m is the mass of the rocket shell + whatever fuel is in it. 1G = 9.8m/s is the upward acceleration lost to gravity. For model rocketry, you want to design a rocket engine so that the upward acceleration, a, is in the range 5-10 G. This range avoids wasting lots of fuel without requiring you to build the rocket too sturdy.

For NASA moon rockets, a = 0.2G approximately at liftoff increasing as fuel was used. The Saturn V rose, rather majestically, into the sky with a rocket structure that had to be only strong enough to support 1.2 times the rocket weight. Higher initial accelerations would have required more structure and bigger engines. As it was the Saturn V was the size of a skyscraper. You want the structure to be light so that the majority of weight is fuel. What makes it tricky is that the acceleration weight has to sit on an engine that gimbals (slants) and runs really hot, about 3000°C. Most engineering projects have fewer constraints than this, and are thus “not rocket science.”

A space rocket has to reach very high, orbital speed if the rocket is to stay up indefinitely, or nearly orbital speed for long-range, military uses. You can calculate the orbital speed by balancing the acceleration of gravity, 9.8 m/s2, against the orbital acceleration of going around the earth, a sphere of 40,000 km in circumference (that’s how the meter was defined). Orbital acceleration, a = v2/r, and r = 40,000,000 m/2π = 6,366,000m. Thus, the speed you need to stay up indefinitely is v=√(6,366,000 x 9.8) = 7900 m/s = 17,800 mph. That’s roughly Mach 35, or 35 times the speed of sound at sea level, (343 m/s). You need some altitude too, just to keep air friction from killing you, but for most missions, the main thing you need is velocity, kinetic energy, not potential energy, as I’ll show below. If your speed exceeds 17,800 m/s, you go higher up, but the stable orbital velocity is lower. The gravity force is lower higher up, and the radius to the earth higher too, but you’re balancing this lower gravity force against v2/r, so v2 has to be reduced to stay stable high up, but higher to get there. This all makes docking space-ships tricky, as I’ll explain also. Rockets are the only way practical to reach Mach 35 or anything near it. No current cannon or gun gets close.

Kinetic energy is a lot more important than potential energy for sending an object into orbit. To get a sense of the comparison, consider a one kg mass at orbital speed, 7900 m/s, and 200 km altitude. For these conditions, the kinetic energy, 1/2mv2 is 31,205 kJ, while the potential energy, mgh, is only 1,960 kJ . The potential energy is thus only 1/16 the kinetic energy.

Not that it’s easy to reach 200 miles altitude, but you can do it with a sophisticated cannon. The Germans did it with “simple”, one stage, V2-style rockets. To reach orbit, you generally need multiple stages. As a way to see this, consider that the energy content of gasoline + oxygen is about 10.5 MJ/kg (10,500 kJ/kg); this is only 1/3 of the kinetic energy of the orbital rocket, but it’s 5 times the potential energy. A fairly efficient gasoline + oxygen powered cannon could not provide orbital kinetic energy since the bullet can move no faster than the explosive vapor. In a rocket this is not a constraint since most of the mass is ejected.

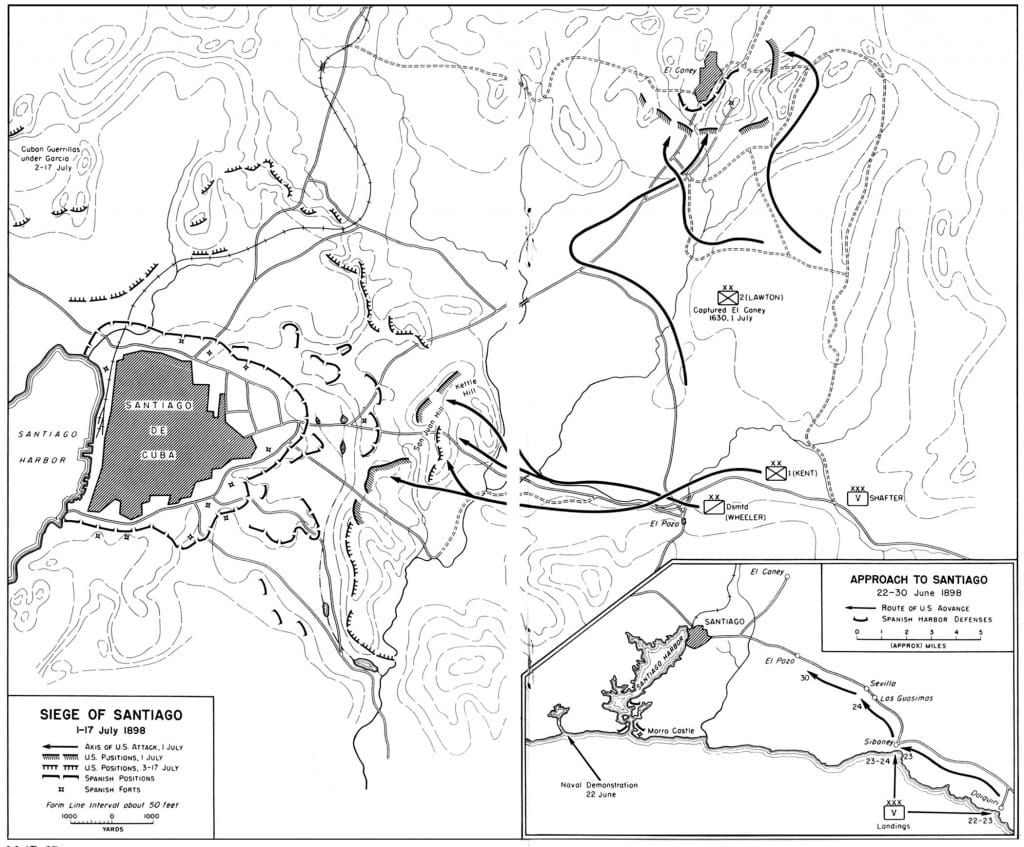

A shell fired at a 45° angle that reaches 200 km altitude would go about 800 km — the distance between North Korea and Japan, or between Iran and Israel. That would require twice as much energy as a shell fired straight up, about 4000 kJ/kg. This is still within the range for a (very large) cannon or a single-stage rocket. For Russia or China to hit the US would take much more: orbital, or near orbital rocketry. To reach the moon, you need more total energy, but less kinetic energy. Moon rockets have taken the approach of first going into orbit, and only later going on. While most of the kinetic energy isn’t lost, it’s likely not the best trajectory in terms of energy use.

The force produced by a rocket is equal to the rate of mass shot out times its velocity. F = ∆(mv). To get a lot of force for each bit of fuel, you want the gas exit velocity to be as fast as possible. A typical maximum is about 2,500 m/s. Mach 10, for a gasoline – oxygen engine. The acceleration of the rocket itself is this ∆mv force divided by the total remaining mass in the rocket (rocket shell plus remaining fuel) minus 1 (gravity). Thus, if the exhaust from a rocket leaves at 2,500 m/s, and you want the rocket to accelerate upward at an average of 10 G, you must exhaust fast enough to develop 10 G, 98 m/s2. The rate of mass exhaust is the average mass of the rocket times 98/2500 = .0392/second. That is, about 3.92% of the rocket mass must be ejected each second. Assuming that the fuel for your first stage engine is less than 80% of the total mass, the first stage will flare-out in about 20 seconds. Typically, the acceleration at the end of the 20 burn is much greater than at the beginning since the rocket gets lighter as fuel is burnt. This was the case with the Apollo missions. The Saturn V started up at 0.5G but reached a maximum of 4G by the time most of the fuel was used.

If you have a good math background, you can develop a differential equation for the relation between fuel consumption and altitude or final speed. This is readily done if you know calculus, or reasonably done if you use differential methods. By either method, it turns out that, for no air friction or gravity resistance, you will reach the same speed as the exhaust when 64% of the rocket mass is exhausted. In the real world, your rocket will have to exhaust 75 or 80% of its mass as first stage fuel to reach a final speed of 2,500 m/s. This is less than 1/3 orbital speed, and reaching it requires that the rest of your rocket mass: the engine, 2nd stage, payload, and any spare fuel to handle descent (Elon Musk’s approach) must weigh less than 20-25% of the original weight of the rocket on the launch pad. This gasoline and oxygen is expensive, but not horribly so if you can reuse the rocket; that’s the motivation for NASA’s and SpaceX’s work on reusable rockets. Most orbital rocket designs require three stages to accelerate to the 7900 m/s orbital speed calculated above. The second stage is dropped from high altitude and almost invariably lost. If you can set-up and solve the differential equation above, a career in science may be for you.

Now, you might wonder about the exhaust speed I’ve been using, 2500 m/s. You’ll typically want a speed at lest this high as it’s associated with a high value of thrust-seconds per weight of fuel. Thrust seconds pre weight is called specific impulse, SI, SI = lb-seconds of thrust/lb of fuel. This approximately equals speed of exhaust (m/s) divided by 9.8 m/s2. For a high molecular weight burn it’s not easy to reach gas speed much above 2500, or values of SI much above 250, but you can get high thrust since thrust is related to momentum transfer. High thrust is why US and Russian engines typically use gasoline + oxygen. The heat of combustion of gasoline is 42 MJ/kg, but burning a kg of gasoline requires roughly 2.5 kg of oxygen. Thus, for a rocket fueled by gasoline + oxygen, the heat of combustion per kg is 42/3.5 = 12,000,000 J/kg. A typical rocket engine is 30% efficient (V2 efficiency was lower, Saturn V higher). Per corrected unit of fuel+oxygen mass, 1/2 v2 = .3 x 12,000,000; v =√7,200,000 = 2680 m/s. Adding some mass for the engine and fuel tanks, the specific impulse for this engine will be, about 250 s. This is fairly typical. Higher exhaust speeds have been achieved with hydrogen fuel, it has a higher combustion energy per weight. It is also possible to increase the engine efficiency; the Saturn V, stage 2 efficiency was nearly 50%, but the thrust was low. The sources of inefficiency include inefficiencies in compression, incomplete combustion, friction flows in the engine, and back-pressure of the atmosphere. If you can make a reliable, high efficiency engine with good lift, a career in engineering may be for you. A yet bigger challenge is doing this at a reasonable cost.

At an average acceleration of 5G = 49 m/s2 and a first stage that reaches 2500 m/s, you’ll find that the first stage burns out after 51 seconds. If the rocket were going straight up (bad idea), you’d find you are at an altitude of about 63.7 km. A better idea would be an average trajectory of 30°, leaving you at an altitude of 32 km or so. At that altitude you can expect to have far less air friction, and you can expect the second stage engine to be more efficient. It seems to me, you may want to wait another 10 seconds before firing the second stage: you’ll be 12 km higher up and it seems to me that the benefit of this will be significant. I notice that space launches wait a few seconds before firing their second stage.

As a final bit, I’d mentioned that docking a rocket with a space station is difficult, in part, because docking requires an increase in angular speed, w, but this generally goes along with a decrease in altitude; a counter-intuitive outcome. Setting the acceleration due to gravity equal to the angular acceleration, we find GM/r2 = w2r, where G is the gravitational constant, and M is the mass or the earth. Rearranging, we find that w2 = GM/r3. For high angular speed, you need small r: a low altitude. When we first went to dock a space-ship, in the early 60s, we had not realized this. When the astronauts fired the engines to dock, they found that they’d accelerate in velocity, but not in angular speed: v = wr. The faster they went, the higher up they went, but the lower the angular speed got: the fewer the orbits per day. Eventually they realized that, to dock with another ship or a space-station that is in front of you, you do not accelerate, but decelerate. When you decelerate you lose altitude and gain angular speed: you catch up with the station, but at a lower altitude. Your next step is to angle your ship near-radially to the earth, and accelerate by firing engines to the side till you dock. Like much of orbital rocketry, it’s simple, but not intuitive or easy.

Robert Buxbaum, August 12, 2015. A cannon that could reach from North Korea to Japan, say, would have to be on the order of 10 km long, running along the slope of a mountain. Even at that length, the shell would have to fire at 450 G, or so, and reach a speed about 3000 m/s, or 1/3 orbital.