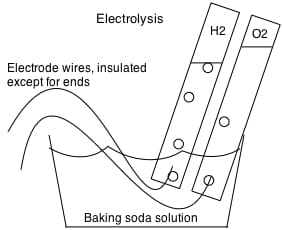

Last week, I submitted a provisional patent application for an improved fuel reformer system to allow a fuel cell to operate on ordinary, liquid fuels, e.g. alcohol, gasoline, and JP-8 (diesel). I’m attaching the complete text of the description, below, but since it is not particularly user-friendly, I’d like to add a small, explanatory preface. What I’m proposing is shown in the diagram, following. I send a hydrogen-rich stream plus ordinary fuel and steam to the fuel cell, perhaps with a pre-reformer. My expectation that the fuel cell will not completely convert this material to CO2 and water vapor, even with the pre-reformer. Following the fuel cell, I then use a water-gas shift reactor to convert product CO and H2O to H2 and CO2 to increase the hydrogen content of the stream. I then use a semi-permeable membrane to extract the waste CO2 and water. I recirculate the hydrogen and the rest of the water back to the fuel cell to generate extra power, prevent coking, and promote steam reforming. I calculate the design should be able to operate at, perhaps 0.9 Volt per cell, and should nearly double the energy per gallon of fuel compared to ordinary diesel. Though use of pure hydrogen fuel would give better mileage, this design seems better for some applications. Please find the text following.

Use of a Water-Gas shift reactor and a CO2 extraction membrane to improve fuel utilization in a solid oxide fuel cell system.

Inventor: Dr. Robert E. Buxbaum, REB Research, 12851 Capital St, Oak Park, MI 48237; Patent Pending.

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) have improved over the last 10 years to the point that they are attractive options for electric power generation in automobiles, airplanes, and auxiliary power supplies. These cells operate at high temperatures and tolerate high concentrations of CO, hydrocarbons and limited concentrations of sulfur (H2S). SOFCs can operate on reformate gas and can perform limited degrees of hydrocarbon reforming too – something that is advantageous from the stand-point of fuel logistics: it’s far easier to transport a small volume of liquid fuel that it is a large volume of H2 gas. The main problem with in-situ reforming is the danger of coking the fuel cell, a problem that gets worse when reforming is attempted with the more–desirable, heavier fuels like gasoline and JP-8. To avoid coking the fuel cell, heavier fuels are typically reforming before hand in a separate reactor, typically by partial oxidation at auto-thermal conditions, a process that typically adds nitrogen and results in the inability to use the natural heat given off by the fuel cell. Steam reforming has been suggested as an option (Chick, 2011) but there is not enough heat released by the fuel cell alone to do it with the normal fuel cycles.

Another source of inefficiency in reformate-powered SOFC systems is basic to the use of carbon-containing fuels: the carbon tends to leave the fuel cell as CO instead of CO2. CO in the exhaust is undesirable from two perspectives: CO is toxic, and quite a bit of energy is wasted when the carbon leaves in this form. Normally, carbon can not leave as CO2 though, since CO is the more stable form at the high temperatures typical of SOFC operation. This patent provides solutions to all these problems through the use of a water-gas shift reactor and a CO2-extraction membrane. Find a drawing of a version of the process following.

RE. Buxbaum invention: A suggested fuel cycle to allow improved fuel reforming with a solid oxide fuel cell

As depicted in Figure 1, above, the fuel enters, is mixed with steam or partially boiled water, and heated in the rectifying heat exchanger. The hot steam + fuel mix then enters a steam reformer and perhaps a sulfur removal stage. This would be typical steam reforming except for a key difference: the heat for reforming comes (at least in part) from waste heat of the SOFC. Normally speaking there would not be enough heat, but in this system we add a recycle stream of H2-rich gas to the fuel cell. This stream, produced from waste CO in a water-gas shift reactor (the WGS) shown in Figure 1. This additional H2 adds to the heat generated by the SOFC and also adds to the amount of water in the SOFC. The net effect should be to reduce coking in the fuel cell while increasing the output voltage and providing enough heat for steam reforming. At least, that is the thought.

SOFCs differ from proton conducting FCS, e.g. PEM FCs, in that the ion that moves is oxygen, not hydrogen. As a result, water produced in the fuel cell ends up in the hydrogen-rich stream and not in the oxygen stream. Having this additional water in the fuel stream of the SOFC can promote fuel reforming within the FC. This presents a difficulty in exhausting the waste water vapor in that a means must be found to separate it from un-combusted fuel. This is unlike the case with PEM FCs, where the waste water leaves with the exhaust air. Our main solution to exhausting the water is the use of a membrane and perhaps a knockout drum to extract it from un-combusted fuel gases.

Our solution to the problem of carbon leaving the SOFC as CO is to react this CO with waste H2O to convert it to CO2 and additional H2. This is done in a water gas shift reactor, the WGS above. We then extract the CO2 and remaining, unused water through a CO2- specific membrane and we recycle the H2 and unconverted CO back to the SOFC using a low temperature recycle blower. The design above was modified from one in a paper by PNNL; that paper had neither a WGS reactor nor a membrane. As a result it got much worse fuel conversion, and required a high temperature recycle blower.

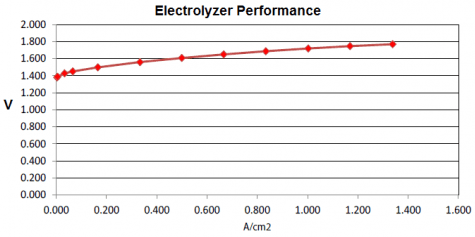

Heat must be removed from the SOFC output to cool it to a temperature suitable for the WGS reactor. In the design shown, the heat is used to heat the fuel before feeding it to the SOFC – this is done in the Rectifying HX. More heat must be removed before the gas can go to the CO2 extractor membrane; this heat is used to boil water for the steam reforming reaction. Additional heat inputs and exhausts will be needed for startup and load tracking. A solution to temporary heat imbalances is to adjust the voltage at the SOFC. The lower the voltage the more heat will be available to radiate to the steam reformer. At steady state operation, a heat balance suggests we will be able to provide sufficient heat to the steam reformer if we produce electricity at between 0.9 and 1.0 Volts per cell. The WGS reactor allows us to convert virtually all the fuel to water and CO2, with hardly any CO output. This was not possible for any design in the PNNL study cited above.

The drawing above shows water recycle. This is not a necessary part of the cycle. What is necessary is some degree of cooling of the WGS output. Boiling recycle water is shown because it can be a logistic benefit in certain situations, e.g. where you can not remove the necessary CO2 without removing too much of the water in the membrane module, and in mobile military situations, where it’s a benefit to reduce the amount of material that must be carried. If water or fuel must be boiled, it is worthwhile to do so by cooling the output from the WGS reactor. Using this heat saves energy and helps protect the high-selectivity membranes. Cooling also extends the life of the recycle blower and allows the lower-temperature recycle blowers. Ideally the temperature is not lowered so much that water begins to condense. Condensed water tends to disturb gas flow through a membrane module. The gas temperatures necessary to keep water from condensing in the module is about 180°C given typical, expected operating pressures of about 10 atm. The alternative is the use of a water knockout and a pressure reducer to prevent water condensation in membranes operated at lower temperatures, about 50°C.

Extracting the water in a knockout drum separate from the CO2 extraction has the secondary advantage of making it easier to adjust the water content in the fuel-gas stream. The temperature of condensation can then be used to control the water content; alternately, a separate membrane can extract water ahead of the CO2, with water content controlled by adjusting the pressure of the liquid water in the exit stream.

Some description of the membrane is worthwhile at this point since a key aspect of this patent – perhaps the key aspect — is the use of a CO2-extraction membrane. It is this addition to the fuel cycle that allows us to use the WGS reactor effectively to reduce coking and increase efficiency. The first reasonably effective CO2 extraction membranes appeared only about 5 years ago. These are made of silicone polymers like dimethylsiloxane, e.g. the Polaris membrane from MTR Inc. We can hope that better membranes will be developed in the following years, but the Polaris membrane is a reasonably acceptable option and available today, its only major shortcoming being its low operating temperature, about 50°C. Current Polaris membranes show H2-CO2 selectivity about 30 and a CO2 permeance about 1000 Barrers; these permeances suggest that high operating pressures would be desirable, and the preferred operation pressure could be 300 psi (20 atm) or higher. To operate the membrane with a humid gas stream at high pressure and 50°C will require the removal of most of the water upstream of the membrane module. For this, I’ve included a water knockout, or steam trap, shown in Figure 1. I also include a pressure reduction valve before the membrane (shown as an X in Figure 1). The pressure reduction helps prevent water condensation in the membrane modules. Better membranes may be able to operate at higher temperatures where this type of water knockout is not needed.

It seems likely that, no matter what improvements in membrane technology, the membrane will have to operate at pressures above about 6 atm, and likely above about 10 atm (upstream pressure) exhausting CO2 and water vapor to atmosphere. These high pressures are needed because the CO2 partial pressure in the fuel gas leaving the membrane module will have to be significantly higher than the CO2 exhaust pressure. Assuming a CO2 exhaust pressure of 0.7 atm or above and a desired 15% CO2 mol fraction in the fuel gas recycle, we can expect to need a minimum operating pressure of 4.7 atm at the membrane. Higher pressures, like 10 or 20 atm could be even more attractive.

In order to reform a carbon-based fuel, I expect the fuel cell to have to operate at 800°C or higher (Chick, 2011). Most fuels require high temperatures like this for reforming –methanol being a notable exception requiring only modest temperatures. If methanol is the fuel we will still want a rectifying heat exchanger, but it will be possible to put it after the Water-Gas Shift reactor, and it may be desirable for the reformer of this fuel to follow the fuel cell. When reforming sulfur-containing fuels, it is likely that a sulfur removal reactor will be needed. Several designs are available for this; I provide references to two below.

The overall system design I suggest should produce significantly more power per gm of carbon-based feed than the PNNL system (Chick, 2011). The combination of a rectifying heat exchange, a water gas reactor and CO2 extraction membrane recovers chemical energy that would otherwise be lost with the CO and H2 bleed steam. Further, the cooling stage allows the use of a lower temperature recycle pump with a fairly low compression ratio, likely 2 or less. The net result is to lower the pump cost and power drain. The fuel stream, shown in orange, is reheated without the use of a combustion pre-heater, another big advantage. While PNNL (Chick, 2011) has suggested an alternative route to recover most of the chemical energy through the use of a turbine power generator following the fuel cell, this design should have several advantages including greater reliability, and less noise.

Claims:

1. A power-producing, fuel cell system including a solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) where a fuel-containing output stream from the fuel cell goes to a regenerative heat exchanger followed by a water gas shift reactor followed by a membrane means to extract waste gases including carbon dioxide (CO2) formed in said reactor. Said reactor operating a temperatures between 200 and 450°C and the extracted carbon dioxide leaving at near ambient pressure; the non-extracted gases being recycled to the fuel cell.

Main References:

The most relevant reference here is “Solid Oxide Fuel Cell and Power System Development at PNNL” by Larry Chick, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory March 29, 2011: http://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/03/f10/apu2011_9_chick.pdf. Also see US patent 8394544. it’s from the same authors and somewhat similar, though not as good and only for methane, a high-hydrogen fuel.

Robert E. Buxbaum, REB Research, May 11, 2015.