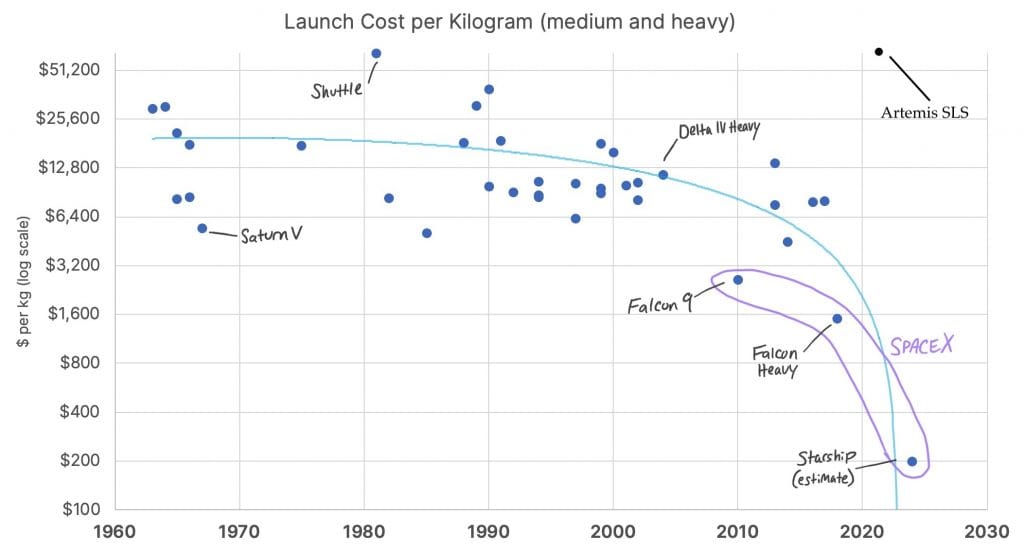

This week, the Artemis I, Orion capsule splashed down to general applause after circling the moon with mannequins. The launch cost $4.1 Billion, and the project, $50 Billion so far, of $93 Billion expected. Artemis II will carry people around the moon, and Artemis III is expected to land the first woman and person of color. The goal isn’t one I find inspiring, and I feel even less inspired by the technology. I see few advances in Artemis compared to the Saturn V of 50 years ago. And in several ways, it looks like a step backwards.

The graphic below compares the Artemis I SLS (Space Launch System) to the Saturn V. The SLS is 10% lighter, but the payload is lighter, too. It can carry 27 tons to the moon, while the Saturn V sent 50 tons to the moon. I’d expect more weight by now. We have carbon fiber and aramids, and they did not. Add to this that the cost per flight is higher, $4.1 B, versus $1.49 B in 2022 dollars for a Saturn V ($185 million in 1969 dollars). What’s more there was no new engine development or production, so the flight numbers are limited: Each SLS launch throws away five, space shuttle engines. When they are all gone, the project ends. We have no plans or ability to make more engines.

As it happens, there was a better alternative available, the Falcon heavy from SpaceX. The Falcon heavy has been flying for 5 years now, and costs only $141 million per launch, about 1/30 as much as an Artemus launch. The rocket is largely reusable, with 3D printed engines, and boosters that land on their tails. Each SLS is expensive because it’s essentially a new airplane built specially for each flight. Every part but the capsule is thrown away. Adding to the cost of SLS launches is the fuel; hydrogen, the same fuel as the space shuttle. Per energy it’s very expensive. The energy cost for the SLS boosters is high too, and the efficiency is low; each SLS booster costs $290M, more than the cost of two Falcon heavy launches. Falcon launches are cheap, in part because the engines burn kerosine, as did the Saturn V at low altitude. Beyond cost hydrogen has low thrust per flow (low momentum), and is hard to handle; hydrogen leaks caused two Artemis scrubs, and numerous Shuttle delays. I discussed the physics of rocket engines in a post seven years ago.

It might be argued that Artemis SLS is an inspirational advance because it can lift an entire moon project in one shot, but the Saturn V lifted that and more, all of Skylab. Besides, there is no need to lift everything on one launch. Elon Musk has proposed lifting in two stages, sending the moon rocket and moon lander to low earth orbit with one launch, then lifting fuel and the astronauts on a second launch. Given the low cost of a Falcon heavy launch, Musk’s approach is sure to save money. It also helps develop space refueling, an important technology.

Musk’s Falcon may still reach the moon because NASA still needs a moon lander. NASA has awarded the lander contract to three companies for now, Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin, Dynetics-Aerodyne makers of the Saturn V, and Musk’s SpaceX. If the SpaceX version wins, a modified Falcon will be sent to the moon on a Falcon heavy along with a space station. Artemis III will rendezvous with them, astronauts will descend to the moon on the lander, and will use the lander to ascend. They’ll then transfer to an Orion capsule for the return journey. NASA has also contracted with Bezos’s Blue origin for planetary, Earth observation, and exploration plans. I suspect that Musk’s lander will win, if only because of reliability. There have been 59 Falcon launches this year, all of them with safe landings. By contrast, no Blue Origin or Dynetics rocket has landed, and Blue Origin does not expect to achieve orbital velocity till 2025.

As best I can tell, the reason we’re using the Artemis SLS with its old engines is inspiration. The Artemis program director, Charlie Blackwell-Thompson is female, and an expert in space shuttle engines. Previous directors were male. Previous astronauts too were mostly male. Musk is not only male, but his products suffer from him being considered a horrible person, a toxic male, in the Tony Stark (Iron Man) mold. Even Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson are considered better, though their technology is worse. See my comparison of SpaceX, Virgin Blue, and Blue Origin.

To me, the biggest blocks to NASA’s inspirational aims, in my opinion, are the program directors who gave us the moon landing. These were two Nazi SS commanders (SS Sturmbannführers), Arthur Rudolph and Wernher Von Braun. Not only were they male and white, they were barely Americanized Nazis, elevated to their role at NASA after killing off virtually all of their 20,000, mostly Jewish, slave workers making rockets for Hitler. Here’s a song about Von Braun, by Tom Lehrer. Among those killed was Von Braun’s professor. In his autobiography, Von Braun showed no sign of regret for any of this, nor does he take blame. The slave labor camp they ran, Dora-Mittelbau, had the highest death rate of all slave labor camps, and when some workers suggested that they could work better if they were fed, the directors, Rudolph and Von Braun had 80 machine gunned to death. Still, Von Braun got us to the moon, and his inspirational comments line the walls at NASA, Kennedy. Blackwell-Thompson and Bezos are surely more inspirational, but their designs seem like dead ends. We may still have to use Musk’s SpaceX if we want a lander or a moon program after the space shuttle’s engines are used up. As Von Braun liked to point out, “Sacrifices have to be made.”

Robert Buxbaum, December 21, 2022. Here’s a bit more about Rudolph, von Braun, the Peenemünda rocket facility, and the Dora-Mittelbau slave labor camp. I may post photos of Von Braun with Hitler and Himmler in SS regalia, but feel uncomfortable doing so at the moment. I feel similarly about posting links to Von Braun’s inspirational interviews.

is

is  and

and  can be understood as an attraction force between molecules and a molecular volume respectively. Alternately, they can be calculated from the

can be understood as an attraction force between molecules and a molecular volume respectively. Alternately, they can be calculated from the