I’ve written a fair amount about sewage over the years, including the benefits of small dams, and problems of combined sewers, but I thought I’d write here about something really fundamental: sewage has two components, poop and rain, and they should be kept separate. The poop and related liquids are known as sanitary sewage. Ideally it is the treated, saved and used as fertilizer. Rain, known as storm sewage, needs to go to the rivers at a controlled speed, unmixed with sanitary sewage. Sorry to say, in many counties, mine included, the two are mixed following every rain, costing us unnecessary money, and making swimming unsafe, and boating (sometimes) unpleasant.

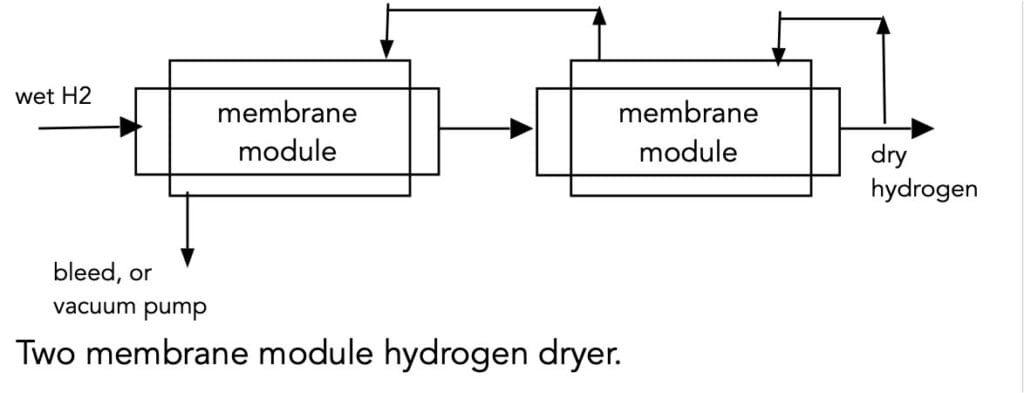

Our system is not quite mixed, but is semi-separate. It only mixes in a “big” rain, more than 1/2″, something that happens once per month, on average. The Pipes are semi-connected as shown below.

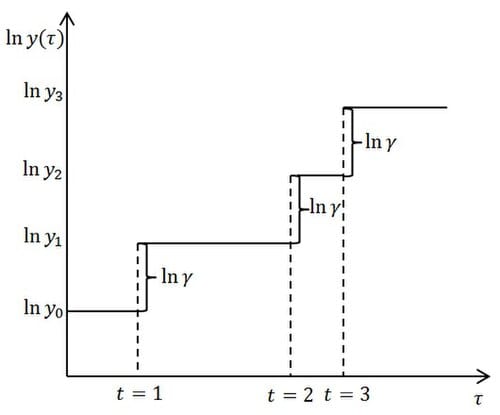

The pipes of a sanitary sewage system can be relatively small in diameter as this flow is continuous, but never that large. The cost of treatment is high, per gallon though. Some of this cost can be recovered in fertilizer value.

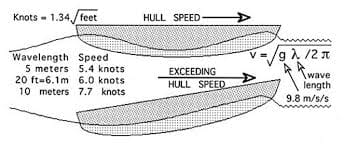

Stormwater flow, by contrast, requires big pipes because the flow, while episodic and be 10,000 more than the sanitary flow. A city can go for weeks without storm flow as there’re is no rain. A storm will then drop more water in an hour than all the sanitary sewage of the last few weeks. You need large diameter stormwater pipes, and you typically want retention basins so that even these pipes are not overwhelmed, and to provide a little settling. The pipes should direct storm water to the nearest river. In our county we mixed the two for historical reasons. This adds tremendously to the cost of sewage treatment, and we find we regularly overwhelm the treatment facility. When this happens, as shown above, sanitary sewage is flushed into the riveras I described ten years ago in a post focussed on pollution from combined sewers. If the rains are really heavy, they back up “sanitary” sewage into basements as well. More commonly, once or twice a month where I live, we just pollute the river. Several cities with combined sewers have separated them recently. Paris, for example, ahead of the 2024 Summer Olympics.

To get an idea of the relative size of the flows in our county, note that Oakland county is a square 30 miles by 30 miles. That’s 900 square miles, or 25.1 billion square feet. In th4e event of a, not uncommon, 2″ rain on this area, we must deal with 4.2 billion cubic feet of water or 33 billion gallons. Some of this absorbs into the ground, but much of it runs goes to pipes heading to the rivers. Ideally we retain some of it above ground for an hour or more because the pipes can’t handle this flow. Even with retention, our rivers rise some 10 feet typically and begin to flow at many miles per hour after a storm. They can be seen carrying trees along, and massively eroding the soil, even in areas that were prepared appropriately.

Sanitary sewage flows are far less voluminous. Our county has roughly 1 million people who flush about 100 million gallons per day, generally sending this to our sanitary sewage treatment plants. That averages a mere 4 million gallons per hour, or 500,000 cubic feet. That’s roughly 8000 times less flow than the storm flow. If any significant fraction of the rainwater goes into our sanitary system, it will quickly overwhelm it and back up into our basements.

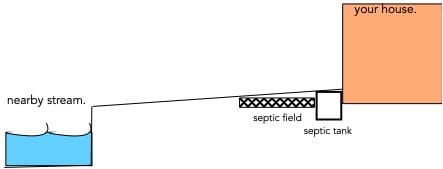

Many people try to get out of paying the high price for municipal sewage treatment by making their own small system with a septic tank an a septic field. I think this is a great idea, a benefit for them and the county. I will be happy to direct them to appropriate educational materials so that home waste flows to the septic tank where anaerobic bacteria break things down, it should then flow to a septic field that filters the nutrients and allows aerobic bacteria to break things down further. Nutrients in the sewage helps whatever you plant and, as we say, “the grass is always greenest over the septic tank.” As for the county on the whole, I wish we got real value from the fertilizer, as Milwaukee does, and wish we’d separate the sewers.

Robert Buxbaum, February 23, 2025