CPAP machines (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure machines) are very commonly prescribed to prevent sleep apnea. They were originally prescribed to prevent heart attack, and despite minimal evidence that they help, they are still paid for by most insurance, including medicare. Sleep apnea is associated with snoring and with being overweight. The theory, supported by minimal evidence, was that stopping the apnea would prevent heart attack.

Five years ago, I found myself among those prescribed. CPAP, and found no evidence they extended life, or prevented any heart problem. I wrote this blog post, explaining what I thought was going on. I suspected some health risks, and found no obvious sleep benefit; I felt claustrophobic and woke with sniffles. I quickly stopped using the device.

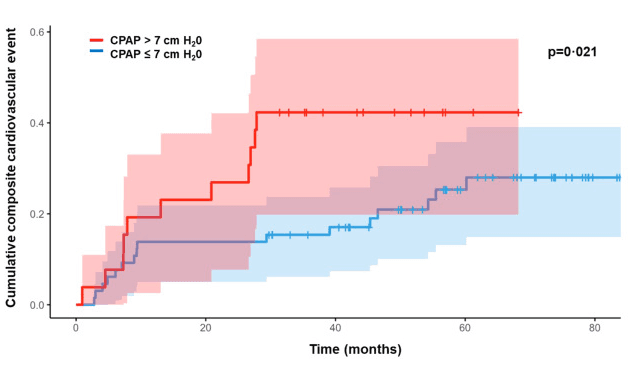

Last month I retried my CPAP, now with a better fitting mask (nose only) and better humidification. I now find sleep benefits and no sniffles, but still see no sign of health benefits. “Even among participants with good CPAP adherence there was no significant reduction in cardiovascular risk in the two largest trials.2,3 ” There also appear to be some bad side effects. If the pressures are too high, the CPAP can cause inflammation and micro-tears in the lung. This is the same problem that killed people on ventilators during COVID. CPAP users show significantly increased inflammation markers, with higher inflammation the higher the pressure used. Lower pressure settings seems to result in fewer heart problems, too, see figure below. The number of cumulative adverse heart-events is lower for patients, randomly selected, who used a pressure below 7 cm H2O (lower than 0.1 psi). Most events happen in the first few months, and don’t know why. The researchers do not comment on this.

I suspect that heart attack and stroke are mostly driven by BMI, lack of exercise, and by eating too much of the wrong foods (e.g. waffles, see here). I suspect the CPAP does nothing for this beyond improved sleep, and that, at the current pressure settings, it may be harmful.The health risks might have put me off the machine, except I like getting better sleep.

I figured I could try decreasing the pressure, hoping to get good sleep with fewer lung risks. I can’t reduce usage because healthcare pays for supplies only if you use the device 4+ hours per night, tracking your usage over the internet to make sure. I discovered that my device, an AirSense 10, was set to deliver pressures between 5 and 15 cmH2O resulting in an average delivery pressure of 10.2 cmH2O. I decreased the range to 4.6-12.4 cm, then further, to 5-9 cmH2O. So far, the machine shows no reduction in average pressure(?!) but my sleep is OK.

On a national level, I suspect that this device should not be prescribed as often as it is, and suspect that the set pressures should be lower. There is a replication crisis in science; drug statistics tend to be bogus, and food results too. If it were me I’d look for CPAP research to show real health benefits, I’d use linear regression with an r-squared test for significance, as here.

Robert Buxbaum, March 30, 2025.